Troubleshooting Chalk Gesso

December 14, 2010

The first time I began creating paintings on panels using chalk gesso I had no problems. I read the manuals, ordered the materials from a good supplier in NYC and proceeded to create my panels. No problem. It was summer in Connecticut. 30 years on, the paintings I created from those panels are still alive and well.

Over the years, with other batches both in sunny, dry, warm California and later in Germany (also in the summertime), I had no problem. My batches were done using rabbitskin glue sourced from my American art suppliers (Utrecht in NYC or Bay City in SF) or later Kremer pigmente in Munich. Now, after moving to Bruges, I’m back to creating new batches of gessoed panels. But why am I experiencing such difficulty with my gesso? How strange to find myself returning to square one with what should be a relatively simple process. So, I’ve decided to document my trials and errors – for myself and internet posterity. There may be others out there who have experienced similar problems?

The problem:

My assembly process would begin normally, but as I proceeded to build up layers, the gesso would no longer flow but rather glom onto the panel. The brush would stick, the gesso would glob. When dry, a little sandpaper would remove far too much pigment. So it was clear: there was a problem with my glue.

Troubleshooting:

I generally create my panels in the wintertime. Nothing to be done about that. The house is radiator heated, that’s got to be better than whatever (winter) conditions Cennini ever experienced. We live next to a canal in an older house that does not contain double glazed windows, so it might be more drafty and moist than many modern environments, still, creating good gesso panels should be possible.

Double boiler? Yes, of course. Did the glue boil? No. Never. But after the gelatine melts, what is the threshhold temperature which spoils the glue? I researched temps on the internet and found 52° Centigrade to be the most generally noted gauge. But is that true? From my experience, it depends on the source, as RS can vary a great deal. At this point, I would not go by numbers but rather my own eyesight.

For example, a few years ago I bought a new batch of glue from my local art dealer, a man who specialized in esoteric artists materials. It seemed OK at the time but then the problem began to recur. Does RS have a shelf life? Or did I let the glue “cook” too long? I had purchased a meat thermometer and kept my temp well below 52°. Still, invasion of the glom.

For my most recent batch I used the last of my old RS from the esoteric art supply store. When I added the pigment, the paint became very granular and unattractive. I guess it does have a shelf life (even though it did not smell)… So I threw it out.

Then used the RS that I had purchased recently from Kraemer Pigmente. Little crystalline pebbles, very nice. When I ran out of the Kraemer RS (silly, I had only purchased a 100 G test amount), I bought a new batch of glue from my local art supply store (brand, Senellier). This stuff comes in pellets similar to the scat of small animals that you might find in a forest. (I prefer the Kraemer) But for both glues, I soaked them overnight (80 G RS to 1 liter of water), melted, cooled and did the finger-pressure-crevice test. So far, so good. (Though the Kraemer RS seemed firmer, clearer, less cloudy, more uniform and refined.)

I bought an electric warming plate at the local Kringwinkel (Salvation Army). It holds food warm but doesn’t cook it. 40° Centigrade or so but not higher. Great, I thought. But still, when I kept the glue-pigment in that double boiler pot for a few hours, the glue lost its strength. Oooops.

*Update from 2019. I coated about 50 small panels in traditional chalk gesso in my studio July-August 2019. I was extremely careful to melt the rabbit skin glue, add the calcium carbonate (with 10% titanium white) and create a thin creamlike consistency of my gesso. I kept it in a large jar in a double boiler bath. As soon as the glue melted and achieved the right consistency, I would remove it from the heat. I worked quickly to cover my (3 mm HDF) panels front and back, so was intent on completing the 10 thin coats in one day’s working session. I reheated my gesso as necessary (when the RS glue began to thicken) but was careful to not let it “cook”. My panels turned out fine. I’m thinking that the problems I had before were due to in attentiveness on my part. I must have allowed the glue to sit too long on the heat, adversely affecting the integrity of the RS glue. Also, completing the panels in one day’s working session insures the right amount of evaporation to contribute to the binding of one coat to its successor.

Bottom line:

- Buy the best grade of RS that you can find from an archival artist’s materials supplier (like Kraemer).

- Do the crevice test, if you want, but be sure to take it off the heat as soon as it fully melts.

- Add your pigment in the center in a stream, allowing it to gently absorb the glue and sink via gravity.

- Stir thoroughly but not vigorously.

- For uniformity, do your gessoing in one session (one day).

- Rabbitskin glue is an organic substance, containing all the resilience and receptivity of living matter, as well as it’s limitations.

The Inside-Out: final version

October 17, 2010

A few years ago I located a couple of carpenters who spoke enough English (and were pretty good at sign-language) to readily understand what I wanted them to create. A few weeks later they contacted me, “het is klaar” (it’s ready). My concept: I wanted to create a two sided painting (on a wooden panel) with a rotating inner core. The core needed to be extractable duing my creation process but afterwards could be fixed (permanently) in place.

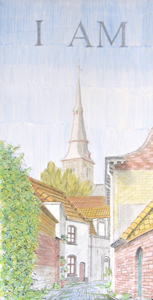

But why create two paintings on one panel? It’s a ton of work. And what would be the reward? That’s very hard to say, except this: it’s a clear and definite way to demonstrate relation. Relation of what to what? You choose, but of course it offered the fundamental and very pregnant possibility of contrasting realism with abstraction in a direct and visceral way. For one side, I chose a landscape. A realistic, almost academic landscape based upon a value study of one of my favorite views of the Predijkherrenrij here in Bruges, Belgium.

But why create two paintings on one panel? It’s a ton of work. And what would be the reward? That’s very hard to say, except this: it’s a clear and definite way to demonstrate relation. Relation of what to what? You choose, but of course it offered the fundamental and very pregnant possibility of contrasting realism with abstraction in a direct and visceral way. For one side, I chose a landscape. A realistic, almost academic landscape based upon a value study of one of my favorite views of the Predijkherrenrij here in Bruges, Belgium.

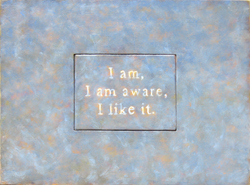

And for the other side? Initially, and for a long time, I planned on an open blue field containing a text from Nisargadatta Maharaj, “I am, I am aware, I like it.” My thinking was simply this: if you have to use words to convery your intent, then these words from Maharaj summarize just about all that you ever really need to know. So, that’s what I created.

And for the other side? Initially, and for a long time, I planned on an open blue field containing a text from Nisargadatta Maharaj, “I am, I am aware, I like it.” My thinking was simply this: if you have to use words to convery your intent, then these words from Maharaj summarize just about all that you ever really need to know. So, that’s what I created.

When the inner core was rotated, it offered views as seen here left and right:

Thus, so far so good, kinda, but the text really bugged me. It took up way too much mental activity – thus creating a tendency to negate not only the unique mental-activity-bypass possibilities of the visual arts, but also the inner intent of the quotation itself! So last week, I painted over the text, to render a pure open field of blue. Ahhhhhh…

When the inner core was rotated into “reality” I got this revised version as seen here left and right. Double ahhhhhhh……. Mucho bueno.

Seeing red

July 9, 2010

Well, OK. Since I started documenting this current production series with the yellow level, I thought I’d continue with the red. Usually, when I trace the development of a painting through its different stages, the thread is the image. But this time the common denominator is color. So, its a different focus, a different challenge. Comparing chromatic qualities instead of developmental ones.

Well, OK. Since I started documenting this current production series with the yellow level, I thought I’d continue with the red. Usually, when I trace the development of a painting through its different stages, the thread is the image. But this time the common denominator is color. So, its a different focus, a different challenge. Comparing chromatic qualities instead of developmental ones.

The Sint AnnaKerk piece is shifting towards purple now. This seems to be due to the combination received through the massive amounts of warm gray tints that I worked into the crimson lake (red) tint. The church was a lovely yellow but I decided it needed a darker more massive tonality in order to provide enough contrast and mass for the strong highlights on its right side. I used clear glaze to eliminate the red tint from most of the green areas. The composition does not have a lot of strong color statements, so it’s interesting to attempt to pull out whatever is possible.

The Predijkherenrij Grande has a strong value composition containing a lot of colors. The red level was a marathon session of 14 hours, working the paints in before the medium dried. Applying the tint, erasing the same from the highlights and some greens and then building up the masses with (mostly) semi-opague tints of warm gray and lead white. Strong reds, yellows and oranges were restated with emulsified pigment. It feels quite hot now, doesn’t it?

The Predijkherenrij Grande has a strong value composition containing a lot of colors. The red level was a marathon session of 14 hours, working the paints in before the medium dried. Applying the tint, erasing the same from the highlights and some greens and then building up the masses with (mostly) semi-opague tints of warm gray and lead white. Strong reds, yellows and oranges were restated with emulsified pigment. It feels quite hot now, doesn’t it?

The concept for the Kruispoorte Grande was simple. Could I take the process-color studio painting technique out into plen air? The yellow level had worked out great. But the red level presented challenges because the composition itself doesn’t have a lot of strong reds in it. I found myself making choices between value (warm gray tints) or hue (yellow) statements: always keeping the overall composition in mind. Still, I’m not at all sure this will be a successful approach. Time will tell.

The concept for the Kruispoorte Grande was simple. Could I take the process-color studio painting technique out into plen air? The yellow level had worked out great. But the red level presented challenges because the composition itself doesn’t have a lot of strong reds in it. I found myself making choices between value (warm gray tints) or hue (yellow) statements: always keeping the overall composition in mind. Still, I’m not at all sure this will be a successful approach. Time will tell.

Stay tuned for the next episode…

Recently, I surfed around to see if I could find information relating to a painting process I use which I’ve always called “the mixed technique” or “the mixed method”. I didn’t find much info (in English) using that term, but got a lot more results when I used the term “mische technique”. Although “a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”, I can see that people who want to inform themselves about this particular process of indirect painting could very well find themselves confused (which I have been), not only about the name, but more importantly about its properties. So I thought I’d try to post what I know. I am no expert and make no claims to be so. I’m just an enthusiastic experimenter.

Thus, there appears to be a very specific application of indirect painting currently called the “mische technique” or even the “mischtechnik” (from Wikipedia). It’s described as an attempt to reconstruct the methods of the early Flemish masters by using “egg tempera to build up volume which is then glazed over with oil paints mixed with resin to produce a jewel-like effect”. The contemporary painters Ernst Fuchs, his student Brigid Marlin and the Society of Art of Imagination seem to me to be the most active exponents of this particular method. Although I’m not sure that the Flemish masters used Red, Yellow and Blue for their imprimatura-undercoats (as it is described on a Brigid’s website) nevertheless, their “mische technique” process appears to be highly effective for luminous, surrealistic Dali-esque imagery. If you are drawn to both this kind of subject matter and this manner of execution, I suggest you check out their links.

Near the village, October by George Inness

Yet the super realism of the “mische technique” – as it is presented on the web – is not really my thing. I tend to be drawn to softly abstracted, beautifully modulated, luminous landscape. Think: George Inness. Think: Tonalism and Luminism. Thus I am deeply drawn to a method of indirect painting which takes advantage of building up an image through multiple layers of paint, allowing for transcendent effects of both light and color. And I use something I call the “mixed method” or “mixed technique” to achieve that.

The process I know, which was taught by Nicholas Wacker at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris during the nineteen sixties and seventies, is also called “the mixed technique” or “mixed method” . It, too, is touted as a reconstruction of the methods of the old masters, although I tend to think its application extends far beyond the precise realism of the Flemish school and the modern surrealists of the “mische technique”. The main aspect of this method is the mixing of an emulsion of water and oil which allows for lean, siccative image development through multiple layers of paint: the essence of an indirect technique. It also allows for soft sensuous blending (without contamination) of adjacent color areas (really luscious wet on wet effects). It demands a well considered composition with interesting value development so that you have a good idea of where you intend to go. Nevertheless, many surprising chromatic events occur during the act of painting, making each “alla prima” session an exciting, challenging process of discovery.

So is the “mixed technique” fundamentally different than the “mische technique” as taught by Wacker? No, not really, but instead of egg yolk, alcasit (a methyl cellulose glue) is used to emulsify the painting emulsion – so there is a longer shelf life. Additionally, high quality, lean, tube oil colors can be used and mixed with the painting emulsion. This has the effect of enhancing the flow and siccative qualities of the tube paint, without forcing the laborious work of grinding each pigment into emulsion in order to create paint. The side effect of that being an extended range of quickly available colors along with the acknowledged down side of a probable reduction in the number of layers of paint that are finally possible. Thus, the rule of fat over lean always applies, even though it can be extended.

The bottom line: the term “mixed” or “mische” refers to the mixing or extending of a water based medium like that of egg tempera into the region of oils – and vice versa – that is, limiting the oily quality of an oil paint through applying resins and emulsion so that it, too, can more easily interact and receive the benefits of the leaner application of a water based paint, like that of egg tempera.

the Disadvantages/Requirements

- long learning curve

- patience

- vision

the Advantages:

- luminosity

- surprising “in the moment” color effects

- seductive tactile blending

If there is someone reading this who has more information or experience than I on this subject, please consider yourself more than welcome to comment or correct mine. Thanks…

Painting: backwards and forwards

March 4, 2010

OK, OK, I admit it. I am in love with glazing. Like non-duality, it has the capacity of unifying many disparate elements, without negating them. (And isn’t that wonderful???) As ever, translucency is the key. But the tricky thing is the application. Too much glazing and the painting has a tendency to float off the panel; too little and the thick opaque paint just stays stuck in the mud, reflecting little or no light. Of course, you can see the same principle reflected in people’s lives. Too little inspiration and we have the tendency to stay stuck in our comfortable grooves; too much inspiration – without a transparent application to the mundane activities of living – and that wonderful poetry, lacking substance, falls short of its mark.

I have admired this very colorful alley view of the Sint Anna Kerk in midday light for a number of years now. Over time, I have made watercolor and value studies of it, photographs, too (here is the all important value study). The light at midday creates a strikingly vertical composition. The color relationships of the tile roofs are quite exciting along with the added bonus of it being the only street in Bruges whose street is lined with bricks glazed in blue ceramic. Over time, I collected enough material for a winter studio production this year.

I began the piece by transposing my black and white drawing to a 30 x 60 cm. gessoed panel. I like to use silverpoint for the first level of drawing. It is very soft and can render lots of intimate details. It tends to create an ambience that invites image development. Silverpoint catches well on the toothy gesso, so the mark lands and does not require too much repetitive movement. Then using india ink, I add touches of higher contrast that push forward the gesture of the composition – but only in the foreground. The idea is to build up the visual effects of distance from the get go. Every layer will play a role. So the black and white level sets up the basics. I’ve decided to add “I Am” to the sky. (the decision occurred after I made the photograph, so Photoshop has come to my display rescue) I use egg tempera to set out the basic color relationships. In contrast to the methods of the old masters, who used their underpainting primarily for value work, I bring color in early in order to test out the vibrations – particularly of complimentary colors. I use a limited palette and usually avoid any color mixing on the palette – with the exception of white since I add zinc white to all my colors in order to avoid an oversaturated final painting. At this stage, the colors are light and somewhat pastel-like. With this method of painting, by the time you reach the oil level, you cannot really paint white over a color to lighten it very much as each successive layer adds a layer of darkness, so to speak. You have to to rely as much as possible on the original white of the panel (that’s why I call it painting backwards). When I’m finished with egg tempera, I seal the surface with a light coat of (rabbitskin) glue size. Oil painting with the mixed technique essentially involves alternating transparent glazes with opaque pigments mixed into a painting emulsion. I start with a yellow glaze and then set out bringing the highlights back in. Yellow paint mixed in a series of tints up to white goes back into areas that will contain differing degrees of that color. Warm Gray mixed up in an array of tints is worked back in to shadow blocks, or alternatively into areas of color that will not contain much yellow. At this point, using a large brush, I try to cover most of the panel with emulsion mixed paint. The work goes quickly. In a few hours, I have set the groundwork for both hue and value development. The overall effect is harmonious and low contrast. Because emulsion has been mixed into the paint, the areas of paint blend smoothly into adjacent areas and will dry to the touch within a few days. Between the yellow and the red layer, I decided that the “I Am” text in the sky needed to be more luminous, so using turpentine and a stiff brush, I took the earlier levels of paint away (painting backwards). The text may now seem rather stark but I know that it will be softly blended by the time I am done. On the palette I mix up a series of tints in yellow, red and warm gray. There are about 15 little blobs of paint. I cover the panel with a thin glaze of Crimson Lake and begin working the colors back into the surface. Reclaiming the highlights is best done by removing the red glaze rather than painting emulsified white paint back into it (more painting backwards). Shadows and other colors receive their appropriate tint (the normal approach of painting forwards). Every area should receive some work; if glaze is not painted into, it can become unreceptive to further manipulations in successive layers. The final level is the blue level. I mix up a series of tints of yellow, red, blue and Payne’s Gray (at this stage I switch from Warm Gray to Payne’s as it is more neutral). Now I have about 20 little blobs of paint. I cover the panel with a light glaze of Cyan. This pigment is quite saturated so I am careful to dilute it well and begin painting. I “erase” the glaze from all the strongly highlighted areas. The warm colors of the underpainted tile roofs pop out and glow (very nice!). I reclaim all the neutrals by painting a gray tint back in, beginning from the background and moving forward. Additional colors arise as needed with a brushstroke of the appropriate color. For example, the strong greens of the foreground shadow, left, are aided by its underlying yellow color structure. Soon I have covered most of the panel and am working details back into the foreground. This is the last session: it takes the longest time since it combines the blue color adjustments along with the final gray balance work. I finally step back, satisfied and ready for dinner.

Comments, as usual are welcome…

Painting, Backwards

January 3, 2010

Painting (any painting) always involves pigment mixed into a medium and set upon a ground. The ground is usually white (or possibly even translucent), thus any pigment added to its surface subtracts from its luminosity and is a movement towards darkness. Alternatively stated, light is the source and darkness its covering. Painting reveals light and uses darkness to do so. If the ground is white, then the primal source of light in any painting is its substrate. This being the case, using and manipulating that source of luminosity is of utmost importance. I continually ask myself, is there a way to paint which can maximize the quality of transmissive light in its ground while contrasting it to the reflective quality of opaque pigments? Painting backwards could be one approach. I stumbled upon it by accident. Here’s what happened:

About a year ago, I began preparing a landscape painting in the usual way. First by gessoing a wooden panel, then by transferring my composition to it using silverpoint. The composition was of the canal in front of my house. I had already created a value study as well as a small oil of the same landscape setting. I was well pleased with both works but felt the composition could benefit from a grander view. So I added buildings to the right and left as well as more sky and water in the foreground. This had the effect of deepening the overall perspective. Nice. Additionally, to enhance the depth from the get go, I highlighted the darker contrasts of the foreground using india ink on top of the already established silverpoint drawing. Nice, again.

In order to minimize the number of layers necessary to create an image in oil, I started the underpainting in egg tempera. Rather than mixing a fully saturated color of the chosen pigment for each element in the image, I added white to each color to avoid oversaturated colors in the final painting. (Oversaturated colors can be lethal to the softly diminishing effects of an ephemerally suggested distance: a lesson I had learned the hard way.) So, all the colors were now set up and were rather pastel in character, complimentary color relationships were established, even if at this point they were still rather subtle.

The next step was unifying all the elements by establishing an overall mood. This is usually done by covering the ground with an imprimatura: a diluted oil color washed over the surface to establish a middle tone. So I painted on a brown imprimatura and then wiped it off. A tonality was established, but it wasn’t quite dark enough. I painted on a second layer of imprimatura just to increase the tonality. But then, rather than painting the highlights back in using white pigment, I decided to erase the imprimatura from the highlight areas using turpentine (I already knew exactly where these areas were as they were well articulated in the underdrawing). This erasing was working well, until I accidentally dipped my brush in distilled water instead of turps. My brush began to delete not only the imprimatura, but also the egg tempera underpainting, the india ink, and then the silverpoint, too. Oops!!! Not what I had intended…

Amidst my curses and exclamations, it became clear to me that I needed to continue this treatment to balance out the rest of the composition, a work of about 15 minutes. When I was done, my husband took a look at the painting and said, “I think you’re done.” And it was true.

Comments are welcome…

After years of experimentation and study, I have come to a technique that at least allows for the possibility of fine painting, in my case landscapes. I’ll try to describe it briefly here below using illustrations from a current project, the Sint Anna Kerk here in Brughes. The value study is completed “en plen air”; the studio work is done in the atelier in successive stages, each oil session is completed “alla prima” (within a few hours). The intent is to capture as much spontneity as possible, within the long time frame that defines an indirect technique.

The start is a value study describing mid-afternoon light. It’s usually a simplified version of where I hope to finally go. I consider it invaluable for setting up both the composition and tonality of the final piece. This study here is done with pencil, white chalk and ink on standard charcoal paper. Highlights and shadows are developed to render a simple direct statement. Any addition information needed can be augmented from photographs and direct observation, since I live around the corner, though I try more and more to rely on my own pictorial memory.

The start is a value study describing mid-afternoon light. It’s usually a simplified version of where I hope to finally go. I consider it invaluable for setting up both the composition and tonality of the final piece. This study here is done with pencil, white chalk and ink on standard charcoal paper. Highlights and shadows are developed to render a simple direct statement. Any addition information needed can be augmented from photographs and direct observation, since I live around the corner, though I try more and more to rely on my own pictorial memory.

The main elements of the composition are transposed to a panel using line, texture, shading and form. Traditionally, fine drawing pens loaded with india ink are used for transferring the linear, graphical part of the drawing but I have recently been experimenting with using a silverpoint stylus for my underdrawing. The final result is softer, warmer and subtler than india ink (see the grey tones). However, that descriptive subtlety is often lost in the intervening layers of paint, thus, I have begun augmenting the silver point with india ink in order to accentuate the contrasts of the foreground. Thus, distance is described from the beginning in a few ways. The decisions made now guide many aspects of the final result, so it is important to be sure and thus avoid pentimento.

The main elements of the composition are transposed to a panel using line, texture, shading and form. Traditionally, fine drawing pens loaded with india ink are used for transferring the linear, graphical part of the drawing but I have recently been experimenting with using a silverpoint stylus for my underdrawing. The final result is softer, warmer and subtler than india ink (see the grey tones). However, that descriptive subtlety is often lost in the intervening layers of paint, thus, I have begun augmenting the silver point with india ink in order to accentuate the contrasts of the foreground. Thus, distance is described from the beginning in a few ways. The decisions made now guide many aspects of the final result, so it is important to be sure and thus avoid pentimento.

In order to minimize the amount of oil needed to achieve layers of color, I use a traditional egg tempera technique to begin the painting. Oil can be painted over egg (fat over lean), however egg cannot be painted over oil. In addition, egg tempera must be painted on a hard, firm surface, otherwise it will crack, thus the panel is prepared with a traditional gesso surface.

In order to minimize the amount of oil needed to achieve layers of color, I use a traditional egg tempera technique to begin the painting. Oil can be painted over egg (fat over lean), however egg cannot be painted over oil. In addition, egg tempera must be painted on a hard, firm surface, otherwise it will crack, thus the panel is prepared with a traditional gesso surface.

I use the egg tempera technique to indicate basic broad areas of local color. All objects at this point are better stated as pastel suggestions rather than full strong colors. In this version of the Sint Anna Kerk, I have been careful to keep my colors light in order to avoid an oversaturated painting in the middle and background areas. I have learned (the hard way) that control of hue, saturation and value are critical for describing distance. The vibrations of complimentary colors are hinted at but not yet fully explored. Also, I try to use single pigments only for spectral purity; no color mixing is done on the pallette. Colors (like certain greens and oranges) that might require mixing are indicated through separate layers of translucent paint. This layer will be dry to the touch almost immediately, but it should dry at least one week before attempting to work in oil.

Although it may seem like a sin to cover the fine egg tempera painting with a blanket of brown, the imprimatura quickly helps to establish the overall key of the piece as well as to unify any disparate elements. The previous egg tempera layer must be not only completely dried but sealed with a layer of glue size to protect it from the succeeding layers of oil based paints. The lines and colors of the previous layers continue to shine through, adding texture and interest, particularly in the mid tones and shadows. The imprimatura is a mixture of damar varnish, turpentine, and brown pigment (in this case, burnt umber). I brush it on, wait a minute or so and then wipe it off with a dry, lint free, soft clean cloth.

Although it may seem like a sin to cover the fine egg tempera painting with a blanket of brown, the imprimatura quickly helps to establish the overall key of the piece as well as to unify any disparate elements. The previous egg tempera layer must be not only completely dried but sealed with a layer of glue size to protect it from the succeeding layers of oil based paints. The lines and colors of the previous layers continue to shine through, adding texture and interest, particularly in the mid tones and shadows. The imprimatura is a mixture of damar varnish, turpentine, and brown pigment (in this case, burnt umber). I brush it on, wait a minute or so and then wipe it off with a dry, lint free, soft clean cloth.

Since I was very interested to retain the purity of the whites in the highlight areas of the picture, I went back into the fresh imprimatura with a brush dipped in fresh turpentine to remove the brown tint from the highlight areas. My theory/concept is that even though I will be painting over these areas in white oil paint to create mass and to soften edges, whatever is underneath ultimately does matter. If I want to somehow simulate the intensity of pure light – even if it is reflective and not transmissive – then the purity of the original gessoed board is important. I let the imprimatura then dry a day or so, and begin painting in the Mixed Technique.

I squeeze a quantity of cadmium yellow onto the pallette and dip a thin, wide bristle brush into the clear medium (1 part Damar, 1 part Stand Oil, 1 part Turps), then scumble in a very thin coat of yellow over the whole surfce. It sets for a minute or so and then I wipe it back off with a soft, lint free cloth. The idea is to leave some translucent color tint with some tack and work the first levels of oil back into it. Because it’s a panel and not canvas, the tackiness of the oil/varnish medium catches the brush stroke well, functioning like the weave of a canvas in attracting the brushstroke yet leaving no trace of a fabric-like texture.

I squeeze a quantity of cadmium yellow onto the pallette and dip a thin, wide bristle brush into the clear medium (1 part Damar, 1 part Stand Oil, 1 part Turps), then scumble in a very thin coat of yellow over the whole surfce. It sets for a minute or so and then I wipe it back off with a soft, lint free cloth. The idea is to leave some translucent color tint with some tack and work the first levels of oil back into it. Because it’s a panel and not canvas, the tackiness of the oil/varnish medium catches the brush stroke well, functioning like the weave of a canvas in attracting the brushstroke yet leaving no trace of a fabric-like texture.

At this stage, I work with two basic colors, yellow and gray. I mix up a gray to match the same value of the pure cadmium yellow medium, in order to set the overall darkest value. I then mix up a series of tints (5 or 6 steps) from both the gray and the yellow to white. I begin painting in large areas trying to quickly cover the whole painting with one of these tints, using a thick bristle brush and an emulsion for the pigments (1 methyl cellulose glue, .5 oil/.5 varnish, 1 water) which hastens the drying time. The drawing and egg tempera levels have already set the stage, so to speak, and function not only as guides but also as mirror like reflections. It takes only a few strokes to bring out a form. I use a fan shaped dry brush to merge forms together.

It’s fine to be working with a limited palette now, thinking ahead by laying in a more saturated yellow for both the greens and the oranges. I use the gray for neutral tonalities, shadow and to suggest distance. The overall contrast is quite low.

I squeeze a small amount of a cool, translucent red pigment out onto a pallette board. In this case I use crimson lake, in the past I have used alizarin crimson. Dipping a wide, flat bristle brush into clear medium (1T,1D,1SO) and then into the pigment, I proceed to scumble a thin layer of translucent red over the entire piece. After a minute or so, I wipe this off with a clean soft cloth, taking off as much pigmented medium as possible. The remaining surface has a slight tack to the touch.

I squeeze a small amount of a cool, translucent red pigment out onto a pallette board. In this case I use crimson lake, in the past I have used alizarin crimson. Dipping a wide, flat bristle brush into clear medium (1T,1D,1SO) and then into the pigment, I proceed to scumble a thin layer of translucent red over the entire piece. After a minute or so, I wipe this off with a clean soft cloth, taking off as much pigmented medium as possible. The remaining surface has a slight tack to the touch.

I mix up three colors this time. Red, in a series of tints up to white. Warm gray mixed in a series of tints up to white and yellow, mixed in the same way. (The value of the pure red is the same value as the pure warm gray, both being close to a pure medium gray value.) Using a big bristle brush and emulsion, I work quickly to re-establish all the values and colors of the intended piece. Occassionally I need to mix a color that requires a combination of two of the premixed tints.

But look, some strong greens are emerging although I haven’t used any green or blue pigment yet! It’s only yellow refracting back through levels of drawing, egg tempera, imprimatura and glaze. Because I use an emulsion (1 methyl cellulose glue, .5 oil/.5 varnish, 1 water) as my painting medium, the work dries quickly, the colors maintain a level of transparency, and the layers of paint are rather lean.

This is the blue level. I premix my intended colors: yellow in a series of 5-6 tints up to white, red, blue and Payne’s gray all mixed in the same way. There are about 20 little blobs of paint, which I may or may not use but I want to be able to work quickly and precisely in my choices.

This is the blue level. I premix my intended colors: yellow in a series of 5-6 tints up to white, red, blue and Payne’s gray all mixed in the same way. There are about 20 little blobs of paint, which I may or may not use but I want to be able to work quickly and precisely in my choices.

I squeeze out a small amount of pure cyan (Thalo Blue) and dip my brush in clear medium (1T, 1V, 1 SO). Cyan is a highly saturated pigment with strong tinting power so a little goes a long way. I scumble it on and after a few moments wipe it back off, leaving a slightly tacky surface that has still more blue in it than I would actually prefer. I remind myself to use Ultramarine Blue next time…

I begin to reclaim the highlights and quarter tones, working with a big brush for starters. Any color I paint now picks up a bit of blue from the glaze. Hmmm…that’s good and it unifies the painting, but is there too much blue? A lot of unexpected colors start to happen. OK, let them emerge. I need to reintroduce the main color contrasts, like the orange for the clay tile roof, the brown bricks and the green vegetation. After the main value and hue statements are set, a few details are reintroduced with a smaller brush to help refine those shapes: window and trim, shadows and highlights. After a few hours, I’ve covered the panel. But is it done?

After the blue session, all the color statements have been made and I’m happy, sort of, but there remains a bluish tint to the whole piece. I could leave it that way, but the intended gray of the church steeple and road pavement encourage me to attempt some gray balance adjustment. So, I cover the entire piece with a clear glaze of medium and wipe it back off (as usual). I mix up a series of tints using Payne’s gray this time as it is both darker and more neutral than the lighter warm gray pigment I have been using. I squeeze out lead white but mix it 50/50 with titanium white; since the painting is moving into it’s oilier stages. I strengthen the pure whites, the gray steeple and pavement, even scumble some body back into the buildings on the shadow side of the street. I put a glaze of yellow on the buildings on the left for local color, and add the final highlights to the tree. There is not much to do, but what is done crisps up value contrasts and defines gray balance.

After the blue session, all the color statements have been made and I’m happy, sort of, but there remains a bluish tint to the whole piece. I could leave it that way, but the intended gray of the church steeple and road pavement encourage me to attempt some gray balance adjustment. So, I cover the entire piece with a clear glaze of medium and wipe it back off (as usual). I mix up a series of tints using Payne’s gray this time as it is both darker and more neutral than the lighter warm gray pigment I have been using. I squeeze out lead white but mix it 50/50 with titanium white; since the painting is moving into it’s oilier stages. I strengthen the pure whites, the gray steeple and pavement, even scumble some body back into the buildings on the shadow side of the street. I put a glaze of yellow on the buildings on the left for local color, and add the final highlights to the tree. There is not much to do, but what is done crisps up value contrasts and defines gray balance.

Eh, voila. C’est fini! The cherries on top are the final touches of gold to the church steeple.

the Indirect Method

May 20, 2009

Indirect painting simply refers to the method of using multiple layers or levels of paint to develop an image. A subset or refinement of indirect painting is the mixed method or mische techinique. The best general description of the indirect painting technique that I know of comes from the out of print book, “The Painter’s Companion: a Basic Guide to Studio Methods and Materials”, by Reed Kay. The book was originally published in 1961 by Webb Books, Inc. and later by Doubleday in 1972 with the new title “The Painter’s Guide to Studio Methods and Materials” .

I have followed his instructions with more and less success for a number of years. I’m hoping to attract others who also have done so and are willing and interested to share their experience. Please use the “Comment” link at the bottom of this article to post questions or experience.

“Indirect Painting

Indirect painting involves procedures in which the final effects in a picture are built up gradually by placing several layers of paint, one over the other, the upper layers modifying, but not altogether concealing, the lower layers.

Indirect painters put their first strokes on the canvas with the expectation that they will paint over them again when they are dry in order to change their effect in some way. Therefore when they put on the first layer of paint, called the underpainting, they do not try for a finished effect, complete in final color, drawing definition, and pattern emphasis. Instead at the beginning of the work they concentrate on one or two of these problems, and they depend upon (and make allowance for) the subsequent layers of paint to develop and modify the underpainting until the remaining problems are finally solved.

Indirect methods of painting have been employed in the past by many artists including Van Eyck, El Greco, and Rembrandt. More recently such painters as Soutine, Modigliani, Rouault, Braque, and Paul Klee have utilized the optical effects of indirect processes.

The existence of indirect painting arises from the fact that although paint may be used opaquely to conceal what is beneath it, it can also be applied so as to be transparent, revealing to a greater or lesser extent what it covers. For example, an oil color, such as cadmium red, in paste consistency may be brushed over an area of thoroughly dried yellow paint. If it is applied evenly and fairly heavily, it will conceal the yellow color entirely. Alternatively the red paint may be thinned with an appropriate diluent and may be spread so thinly over the dried yellow color that it lies over the yellow like a sheet of red cellophane, tinting the area a fiery orange color, while allowing the shape and every surface brush mark on the yellow area to remain visible. The orange tone thus obtained, by superimposing a layer of transparent red on an opaque yellow, will differ considerably in optical character from an orange made by combining the same red and yellow pigments in direct mixture on the palette. The directly mixed tone will have a weighty solid opacity, whereas the orange tone produced through the indirect, or “optical,” mixture of the two colors will have a more luminous vibration, rather like that seen in stained glass when light passes through it.

By exploiting this characteristic of the oil technique, painters found that they could develop a brilliant luminosity whose exact character was unobtainable in the direct techniques. The procedures most commonly used in indirect painting are called glazing and scumbling.

Glazing

A glaze is an almost transparent film of color laid over another paint surface, modifying the original tone of the area. It is usually a dark color placed over a lighter one. Some colors, such as alizarin crimson or viridian green, tend naturally toward a glaze-like transparency. Almost any color can be used as a glaze if it is thinned enough and placed over a lighter tone.

Scumbling

A scumble is related to a glaze in that it is a film of color laid over another paint surface so that it modifies the original color but does not completely conceal it. Unlike a glaze, the scumble is usually a light, semi-opaque color placed over a darker one. Some colors (Naples yellow, for example) are particularly suitable for this technique, but any color may be combined with opaque white and used as a scumble when it is placed over a darker tone. Scumbles are usually characterized by a pearly opalescence or by a soft smoky optical effect.

Mediums

The film of either a glaze or a scumble must be thin enough to allow the paint below it to be visible; otherwise the glaze or scumble would be completely opaque, and its chief characteristic would be lost. The simplest way to obtain the required thin transparent film is to take a little color straight from the tube-for example ultramarine blue-and rub it over a solid, dry, heavily applied area of light underpainting-let us say in this case, pure white. If the blue is scrubbed on vigorously with the brush or rubbed on with a rag or fingertip, it will spread over the white underpainting as a clear transparent tone of rich blue, which can be made lighter the more vigorously it is rubbed and dispersed. The white underpainting must be dry and hard as a rock to withstand the rubbing of the blue paint, or it will smear into the blue and produce a muddy mixture. If the paint is rubbed over too large an area, the binder may be stretched too far and may leave the pigment badly attached to the picture. However, most oil colors now on the market contain sufficient oil to prevent this occurrence.

A different character of glaze or scumble may be obtained by thinning the paint with a diluent or glazing medium, so that it need not be rubbed. This medium may be made up of various combinations of oils, varnishes, and volatile solvents. As in the case of the painting medium, the personal requirements of each artist must determine the exact composition of such a medium. A painter who wishes to glaze rather heavily and to obtain an even vitreous film over an area may want a glaze medium that can be applied evenly and rapidly to the picture surface. The artist may also want the glaze to set quickly so that the picture may be placed upright in a short time without the paint’s trickling. Such rapid setting mediums contain varnish or driers or both, along with the oils, and require a certain skill in handling, since they quickly become tacky and then cannot be reworked or easily removed.

In the original text this formula for a rapid setting medium is given.

- 3 parts by volume stand oil

- 2 parts by volume damar varnish(5-pound cut)

- 3 parts by volume turpentine

- 1 or 2 drops cobalt drier per pint of medium

In present times artists looking for a rapid setting medium would use Liquin by Winsor Newton or Galkyd by Gamblin.

Another painter may prefer a slower setting material so as to be able to deepen or lighten it, remove it or add to it, or reinforce modeling transitions with it. Such a medium might consist solely of stand oil with a little turpentine added.

In general, the less medium used, the better. The glaze or scumble should be made lighter or thinner by dispersing or rubbing rather than by adding excessive amounts of glaze medium as a diluent.

When discussing the merits or disadvantages of a given glazing medium, one must keep in mind the way it is to be used. If only small amounts of medium are added to conventional tube colors, such factors as the yellowing of a particular oil (sun-thickened oil, for example) or the possibility of redissolving a soft resin varnish (such as dammar) are much less hazardous than they would be if the painter were to use large amounts of the medium in proportion to the tube color. The practice of adding glaze mediums to oil paint until it has the consistency of a watercolor wash seems to me to be unnecessary and to magnify all the technical dangers of the oil technique. The desired effects can usually be obtained with less medium and more skill.

Notes

A. The glaze or scumble actually accentuates all brush marks and surface irregularities in the underpainting. Thus the character and direction of all strokes in the underpainting should be meaningful and consistent with the painter’s purpose.

B. Colors diluted with too much glaze medium may trickle. Sometimes such overthinned color develops small spots in the dry film which look like dust spots. Actually they are particles of color clumped together like islands of pigment in a sea of oil.

C. The underpainting must be bone dry before it receives a glaze or scumble.

D. Glazes containing so much medium as to create a glassy surface are dangerous, since subsequent films cannot adhere well to them and must crack at the first movement of the canvas.

E. Glaze films containing high amounts of spirit-resin varnishes (such as dammar) in relation to the oil and pigment content are extremely vulnerable to cleaning operations, since the varnish is always resoluble in the cleaning agents used by most restorers. Glazes that are the final or finishing films on a picture are especially vulnerable since they are usually thin.

F. Pictures glazed with slow-drying colors and very slow-drying mediums (such as walnut oil or poppyseed oil) should be shielded from dirt and dust while they dry.

G. Unsuccessful scumbling or glazing effects may be removed while the glaze is still fresh without disturbing the underpainting by wiping the surface with a clean, soft, lintless rag, moistened, if necessary, with a little turpentine. Such removals are possible only if the underpainting was thoroughly dry before the glaze was applied.

Technical Procedures

Technical complication and variety increase with indirect painting. One method frequently employed may be described in the following general terms:

1. A brush drawing involving only one or two colors is developed to mark out the important locations and divisions on the canvas. The paint is thinned by means of a “lean” medium (such as 1 part sun-thickened oil, 1/2 part varnish, 3 parts turpentine) to a brushable consistency which flows rather easily.

2. The dark and light contrasts are developed by the use of a “lean” fast-drying white (such as flake white) in all the light areas. [Flake White is lead based and therefore rarely used nowadays. Various manufacturers now make alkyd based fast drying whites that are less poisonous]. In the light middle tones the white is mixed slightly with another pigment (ocher, for example, or Indian red). Darks are produced by adding more color or mixed grays to the white, but all darks are kept much lighter than they will appear in the finished painting. The main effort, at this point, is to produce strong placement and gesture of shapes and volumes. These should be expressed broadly with little surface detail but should be accurate as to the relationships of the larger major pictorial masses. At this stage, the effect of this underpainting must be lighter, both in the lights and the darks, than the artist wishes the finished picture to be (Figure 3-16).

3. When this underpainting has dried thoroughly, color relationships are developed over the light monochrome by the use of glazes. These may be brushed on and then modified by wiping them down with a rag or a clean brush so that they emphasize and reinforce the drawing and movement of the underpainting.

4. Color effects are strengthened and made more definite by vigorous direct painting into the glazes (either when the glaze has dried or while it is still wet) with substantial strokes of opaque color. Glazes that have lowered the tone of an area too much may be scumbled over with a lighter color to raise their tonality. Drawing and edges are redefined, especially where glazing or scumbling has caused a passage to lose its initial strength.

Notes

In considering the many possible variations of this procedure, it is wise to keep in mind a few of the possible difficulties.

A. The glaze tends to darken the general tone of the picture. To compensate for this, the underpainting must be kept considerably lighter than the final painting.

B. The glaze and the scumble tend to create soft, unified, diffused effects. Therefore the underpainting should be strong, even somewhat “harder” than the anticipated final effect.

C. If the quality of the glaze is not relieved by some opaque painting and vigorous redrawing, the total effect of the picture may become too washy, spotty, and transparent.

D. In all indirect processes where more than one layer of paint is anticipated, successive layers should be applied “fat over lean.”

Copyright ©1972 by Reed Kay, “The Painter’s Guide to Studio Methods and Materials” (Doubleday & Company)

Silverpoint

May 15, 2009

Hans Holbein silverpoint

Silverpoint is another ancient technique that is receiving renewed attention these days. Jan van Eyck and the Flemish masters are reputed to have regularly used it as a drawing tool. Artists like Picasso and Joseph Stella brought it into the 20th century art world. The final design stands softly but well on its own or can be incorporated as an underdrawing into a painting.

There is an informative site at silverpointweb.com which offers a lot of practical information as well as sales of silver tips and a ground for the drawing support. I bought some of my pure silver tips from him a few years ago. The silver renders a soft, warm gray line that can darken upon exposure to light – just like the silver content of a photograph. The line itself is indelible so it cannot be erased. Another experiential resource is international silverpoint archives.

Drawing with silver is a very simple but time consuming technique. A thin piece of silver is inserted into a drawing stylus instead of a piece of lead. The silver can be obtained from a local silversmith. I have used both pure silver and sterling. The pure silver is reputed to create a slightly darker line, but I have not yet noticed the difference (which could be due to my gessoed surface not having enough tooth, so take my experience with a grain of salt). Points can be chiselled fine or beveled. Darker tones are achieved by repeated gestures and not by an increase in pressure.

silverpoint Joseph Stella

The drawing surface seems to make a great difference in results. The surface should have a slight “tooth” to it, to draw out the silver particles. I have used both white gessoed panels and toned paper. The toned watercolor paper clearly had the tooth to pull out the silver, but the value of the silver was so close to that of the paper that I finally opted for the white panels. Thus far the panels have given fine results which I have then used as underdrawings for some of my paintings.

Gesso

May 9, 2009

Various recipes exist for gesso. Here’s what I use:

The Glue:

Dissolve 2 3/4 ounces of dry rabbit-skin glue with one quart water in a big glass jar (used pickle jars are great for this). This equates to 75 grams dry glue to approximately one liter of distilled water. The proportions work out to approximately 10/1 water to dried glue by volume. Many professional egg tempera painters suggest a higher percentage of 16/1. (I will try this next time around.)

Let it soak overnight.

Heat the glue in a double boiler, that is, with a second pan surrounding the jar with the glue water. The water should be the same temperature as the glue water, so bring the heat up slowly to melt the gelatine glue. Stir gently. The glue should never boil, only melt. Overheating significantly harms the adhesion of the glue, so do not let the temperature rise above 135 F° (57.3 °C), 127F° (53°C) is optimal.

The Filler:

I use calcium carbonate or precipitated chalk or whiting for filler with 10% titanium white or zinc white to insure a bright whiteness to your gesso. The chalk whiting part can vary in both purity and whiteness, depending upon the grade. Industrial grade chalk whiting can be found in most hardware stores or paint shops but I currently buy my calcium carbonate from Kraemer Pigmente. Dry pigments can be found at art supply shops or online suppliers (like Kraemer).

The proportions are 1 lb filler (or 450 grams) to one quart (liter) of glue water. Or 1 1/2 filler to 1 glue water by volume. The chalk is gently poured into the melted glue. I hold a funnel above the glue water, slowly adding the filler. Ideally you should be able to add all the filler in this way until a slight pyramid of filler forms above the fluid surface. Gently stir the mixture, but be careful to avoid creating any air bubbles. They can translate into pinholes in your gesso that are impossible to remove, adversely affecting your pristine starting ground. Lumps can be stirred or strained out (with cheesecloth). The final result should be about the consistency of light cream. Return the mixture to the double boiler (as necessary), keep it warm, but never let it remain too long on the heat as this can adversely affect the integrity of the RS glue.

Applying the Gesso:

Sand the panel lightly to remove any rough texture, clean the dust off with a moist cloth. Cover the board with a light coating of size (1 1/2 oz rabbit skin glue dissolved in one quart water or 45 grams glue to one liter). After the size has dried, begin applying thin coats of gesso. The first coast is loosly brushed or scumbled in. I prefer to apply the gesso to both sides and ends of the panel to avoid any uneven absorption of moisture which might cause warping. I use a wide flat bristle brush (2″), applying thin layers in alternating horizontal and vertical layers. The layers dry quickly, especially in warm weather. Generally a well prepared panel can take about 10 thin coats of Gesso. I wait until 3 or 4 levels have accumulated and begin lightly sanding it down between layers, and then use a moist cloth to remove the dust. For proper adhesion between the layers of gesso it is best to complete your panel in one day’s working session.

Finishing:

After the final coat, the sanding moves from coarse to fine. As a last step, it’s possible to take a slightly damp cloth and rub it gently over the entire surface in circular motions in order to obtain a final smooth, egg shell-like finish. If, however, you intend to use the panel for silver point, it is best to leave that last step out in order to retain a slight tooth to the panel.