I’d rather be blue…

July 14, 2010

My theory of painting is simply this: travelling has to be at least as interesting as finally arriving. It helps to have a numinal idea of what arriving should actually look like, but it wouldn’t be “art” if I already knew, would it? Thus, I always experience a certain kind of hesitancy as I approach the final levels in a painting. Do I really want the journey to end? Will this level “do” it? Or will it need more? And if so: what, where, how? Will the final image end up looking like a bored adult in comparison to its earlier youthful promise? Should I have stopped at some earlier vantage point along the way and just grabbed the ‘chute?

My theory of painting is simply this: travelling has to be at least as interesting as finally arriving. It helps to have a numinal idea of what arriving should actually look like, but it wouldn’t be “art” if I already knew, would it? Thus, I always experience a certain kind of hesitancy as I approach the final levels in a painting. Do I really want the journey to end? Will this level “do” it? Or will it need more? And if so: what, where, how? Will the final image end up looking like a bored adult in comparison to its earlier youthful promise? Should I have stopped at some earlier vantage point along the way and just grabbed the ‘chute?

Additionally, imposing a chromatic structure on image development allows for lots of lateral exploration at each level of additional color. Or to put it in even simpler terms, it helps me to control chaos. Chaos of my own emotions and my emotional reactions either to the subject matter or the developing image in front of my nose. But too much control results in lifelessness, too little, and it’s just chaos.

Additionally, imposing a chromatic structure on image development allows for lots of lateral exploration at each level of additional color. Or to put it in even simpler terms, it helps me to control chaos. Chaos of my own emotions and my emotional reactions either to the subject matter or the developing image in front of my nose. But too much control results in lifelessness, too little, and it’s just chaos.

Riding the surge of that inbetween space, of that wave, is richly rewarding: both exhilirating and terrifying. Committing myself to it involves a kind of surrender and also a kind of trust. If I imagine that the landscape I paint is essentially external to me, if I imagine that the paints I use are essentially “other”, if I imagine that the world itself is not a part of me and myself a part of it, then there is fear.

Riding the surge of that inbetween space, of that wave, is richly rewarding: both exhilirating and terrifying. Committing myself to it involves a kind of surrender and also a kind of trust. If I imagine that the landscape I paint is essentially external to me, if I imagine that the paints I use are essentially “other”, if I imagine that the world itself is not a part of me and myself a part of it, then there is fear.

So, instead of experiencing distance to it all like some alien stranger, I’d rather be blue (thalo or ultramarine, to be exact)…

I am curious, yellow?

June 17, 2010

It isn’t often that I have numerous paintings completed to the same level at the same time. However, since I am preparing for an exposition and have entered into production mode on a number of pieces, right now I have four paintings drying in their yellow stage. There is something particular and special to be seen in these “monochromatic” stages which soon will be integrated into full blown colorful images.

It isn’t often that I have numerous paintings completed to the same level at the same time. However, since I am preparing for an exposition and have entered into production mode on a number of pieces, right now I have four paintings drying in their yellow stage. There is something particular and special to be seen in these “monochromatic” stages which soon will be integrated into full blown colorful images.

It is a curious level, one of overall hue reduction, of lowered value contrast too, of subtle nuances and above YELLOW, contrasted against gray (which of course becomes pushed towards its complement, purple). The underpainted hues that have been developed in the egg tempera stage shine through subtly, as gentle reminders of potential futures, still yet to be heeded or ignored. Who can tell?

It is a curious level, one of overall hue reduction, of lowered value contrast too, of subtle nuances and above YELLOW, contrasted against gray (which of course becomes pushed towards its complement, purple). The underpainted hues that have been developed in the egg tempera stage shine through subtly, as gentle reminders of potential futures, still yet to be heeded or ignored. Who can tell?

Even an abstract background that I know is intended to become a “blue” sky will have elements of the sun’s yellow light within it. If I state it now, it will always be there, ready to rise to the occassion by the brush’s trumpet call.

Even an abstract background that I know is intended to become a “blue” sky will have elements of the sun’s yellow light within it. If I state it now, it will always be there, ready to rise to the occassion by the brush’s trumpet call.

Thus, succcessive stages build back upon the basic statements made in the yellow layer. Warm reds and vibrant greens depend upon a good solid yellow. Yet sometimes, I find myself satisfied with the yellow layer just as it is. Fini. Perhaps it’s only my insatiable curiosity which keeps me wondering about what’s round the next bend, keeping me from lingering with the yellow level and just calling it “done”. So, I document it here: an interesting level, worthy of note, even if today it’s only electronic.

Thus, succcessive stages build back upon the basic statements made in the yellow layer. Warm reds and vibrant greens depend upon a good solid yellow. Yet sometimes, I find myself satisfied with the yellow layer just as it is. Fini. Perhaps it’s only my insatiable curiosity which keeps me wondering about what’s round the next bend, keeping me from lingering with the yellow level and just calling it “done”. So, I document it here: an interesting level, worthy of note, even if today it’s only electronic.

Recently, I surfed around to see if I could find information relating to a painting process I use which I’ve always called “the mixed technique” or “the mixed method”. I didn’t find much info (in English) using that term, but got a lot more results when I used the term “mische technique”. Although “a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”, I can see that people who want to inform themselves about this particular process of indirect painting could very well find themselves confused (which I have been), not only about the name, but more importantly about its properties. So I thought I’d try to post what I know. I am no expert and make no claims to be so. I’m just an enthusiastic experimenter.

Thus, there appears to be a very specific application of indirect painting currently called the “mische technique” or even the “mischtechnik” (from Wikipedia). It’s described as an attempt to reconstruct the methods of the early Flemish masters by using “egg tempera to build up volume which is then glazed over with oil paints mixed with resin to produce a jewel-like effect”. The contemporary painters Ernst Fuchs, his student Brigid Marlin and the Society of Art of Imagination seem to me to be the most active exponents of this particular method. Although I’m not sure that the Flemish masters used Red, Yellow and Blue for their imprimatura-undercoats (as it is described on a Brigid’s website) nevertheless, their “mische technique” process appears to be highly effective for luminous, surrealistic Dali-esque imagery. If you are drawn to both this kind of subject matter and this manner of execution, I suggest you check out their links.

Near the village, October by George Inness

Yet the super realism of the “mische technique” – as it is presented on the web – is not really my thing. I tend to be drawn to softly abstracted, beautifully modulated, luminous landscape. Think: George Inness. Think: Tonalism and Luminism. Thus I am deeply drawn to a method of indirect painting which takes advantage of building up an image through multiple layers of paint, allowing for transcendent effects of both light and color. And I use something I call the “mixed method” or “mixed technique” to achieve that.

The process I know, which was taught by Nicholas Wacker at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris during the nineteen sixties and seventies, is also called “the mixed technique” or “mixed method” . It, too, is touted as a reconstruction of the methods of the old masters, although I tend to think its application extends far beyond the precise realism of the Flemish school and the modern surrealists of the “mische technique”. The main aspect of this method is the mixing of an emulsion of water and oil which allows for lean, siccative image development through multiple layers of paint: the essence of an indirect technique. It also allows for soft sensuous blending (without contamination) of adjacent color areas (really luscious wet on wet effects). It demands a well considered composition with interesting value development so that you have a good idea of where you intend to go. Nevertheless, many surprising chromatic events occur during the act of painting, making each “alla prima” session an exciting, challenging process of discovery.

So is the “mixed technique” fundamentally different than the “mische technique” as taught by Wacker? No, not really, but instead of egg yolk, alcasit (a methyl cellulose glue) is used to emulsify the painting emulsion – so there is a longer shelf life. Additionally, high quality, lean, tube oil colors can be used and mixed with the painting emulsion. This has the effect of enhancing the flow and siccative qualities of the tube paint, without forcing the laborious work of grinding each pigment into emulsion in order to create paint. The side effect of that being an extended range of quickly available colors along with the acknowledged down side of a probable reduction in the number of layers of paint that are finally possible. Thus, the rule of fat over lean always applies, even though it can be extended.

The bottom line: the term “mixed” or “mische” refers to the mixing or extending of a water based medium like that of egg tempera into the region of oils – and vice versa – that is, limiting the oily quality of an oil paint through applying resins and emulsion so that it, too, can more easily interact and receive the benefits of the leaner application of a water based paint, like that of egg tempera.

the Disadvantages/Requirements

- long learning curve

- patience

- vision

the Advantages:

- luminosity

- surprising “in the moment” color effects

- seductive tactile blending

If there is someone reading this who has more information or experience than I on this subject, please consider yourself more than welcome to comment or correct mine. Thanks…

Painting: backwards and forwards

March 4, 2010

OK, OK, I admit it. I am in love with glazing. Like non-duality, it has the capacity of unifying many disparate elements, without negating them. (And isn’t that wonderful???) As ever, translucency is the key. But the tricky thing is the application. Too much glazing and the painting has a tendency to float off the panel; too little and the thick opaque paint just stays stuck in the mud, reflecting little or no light. Of course, you can see the same principle reflected in people’s lives. Too little inspiration and we have the tendency to stay stuck in our comfortable grooves; too much inspiration – without a transparent application to the mundane activities of living – and that wonderful poetry, lacking substance, falls short of its mark.

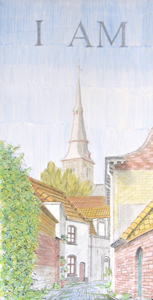

I have admired this very colorful alley view of the Sint Anna Kerk in midday light for a number of years now. Over time, I have made watercolor and value studies of it, photographs, too (here is the all important value study). The light at midday creates a strikingly vertical composition. The color relationships of the tile roofs are quite exciting along with the added bonus of it being the only street in Bruges whose street is lined with bricks glazed in blue ceramic. Over time, I collected enough material for a winter studio production this year.

I began the piece by transposing my black and white drawing to a 30 x 60 cm. gessoed panel. I like to use silverpoint for the first level of drawing. It is very soft and can render lots of intimate details. It tends to create an ambience that invites image development. Silverpoint catches well on the toothy gesso, so the mark lands and does not require too much repetitive movement. Then using india ink, I add touches of higher contrast that push forward the gesture of the composition – but only in the foreground. The idea is to build up the visual effects of distance from the get go. Every layer will play a role. So the black and white level sets up the basics. I’ve decided to add “I Am” to the sky. (the decision occurred after I made the photograph, so Photoshop has come to my display rescue) I use egg tempera to set out the basic color relationships. In contrast to the methods of the old masters, who used their underpainting primarily for value work, I bring color in early in order to test out the vibrations – particularly of complimentary colors. I use a limited palette and usually avoid any color mixing on the palette – with the exception of white since I add zinc white to all my colors in order to avoid an oversaturated final painting. At this stage, the colors are light and somewhat pastel-like. With this method of painting, by the time you reach the oil level, you cannot really paint white over a color to lighten it very much as each successive layer adds a layer of darkness, so to speak. You have to to rely as much as possible on the original white of the panel (that’s why I call it painting backwards). When I’m finished with egg tempera, I seal the surface with a light coat of (rabbitskin) glue size. Oil painting with the mixed technique essentially involves alternating transparent glazes with opaque pigments mixed into a painting emulsion. I start with a yellow glaze and then set out bringing the highlights back in. Yellow paint mixed in a series of tints up to white goes back into areas that will contain differing degrees of that color. Warm Gray mixed up in an array of tints is worked back in to shadow blocks, or alternatively into areas of color that will not contain much yellow. At this point, using a large brush, I try to cover most of the panel with emulsion mixed paint. The work goes quickly. In a few hours, I have set the groundwork for both hue and value development. The overall effect is harmonious and low contrast. Because emulsion has been mixed into the paint, the areas of paint blend smoothly into adjacent areas and will dry to the touch within a few days. Between the yellow and the red layer, I decided that the “I Am” text in the sky needed to be more luminous, so using turpentine and a stiff brush, I took the earlier levels of paint away (painting backwards). The text may now seem rather stark but I know that it will be softly blended by the time I am done. On the palette I mix up a series of tints in yellow, red and warm gray. There are about 15 little blobs of paint. I cover the panel with a thin glaze of Crimson Lake and begin working the colors back into the surface. Reclaiming the highlights is best done by removing the red glaze rather than painting emulsified white paint back into it (more painting backwards). Shadows and other colors receive their appropriate tint (the normal approach of painting forwards). Every area should receive some work; if glaze is not painted into, it can become unreceptive to further manipulations in successive layers. The final level is the blue level. I mix up a series of tints of yellow, red, blue and Payne’s Gray (at this stage I switch from Warm Gray to Payne’s as it is more neutral). Now I have about 20 little blobs of paint. I cover the panel with a light glaze of Cyan. This pigment is quite saturated so I am careful to dilute it well and begin painting. I “erase” the glaze from all the strongly highlighted areas. The warm colors of the underpainted tile roofs pop out and glow (very nice!). I reclaim all the neutrals by painting a gray tint back in, beginning from the background and moving forward. Additional colors arise as needed with a brushstroke of the appropriate color. For example, the strong greens of the foreground shadow, left, are aided by its underlying yellow color structure. Soon I have covered most of the panel and am working details back into the foreground. This is the last session: it takes the longest time since it combines the blue color adjustments along with the final gray balance work. I finally step back, satisfied and ready for dinner.

Comments, as usual are welcome…

After years of experimentation and study, I have come to a technique that at least allows for the possibility of fine painting, in my case landscapes. I’ll try to describe it briefly here below using illustrations from a current project, the Sint Anna Kerk here in Brughes. The value study is completed “en plen air”; the studio work is done in the atelier in successive stages, each oil session is completed “alla prima” (within a few hours). The intent is to capture as much spontneity as possible, within the long time frame that defines an indirect technique.

The start is a value study describing mid-afternoon light. It’s usually a simplified version of where I hope to finally go. I consider it invaluable for setting up both the composition and tonality of the final piece. This study here is done with pencil, white chalk and ink on standard charcoal paper. Highlights and shadows are developed to render a simple direct statement. Any addition information needed can be augmented from photographs and direct observation, since I live around the corner, though I try more and more to rely on my own pictorial memory.

The start is a value study describing mid-afternoon light. It’s usually a simplified version of where I hope to finally go. I consider it invaluable for setting up both the composition and tonality of the final piece. This study here is done with pencil, white chalk and ink on standard charcoal paper. Highlights and shadows are developed to render a simple direct statement. Any addition information needed can be augmented from photographs and direct observation, since I live around the corner, though I try more and more to rely on my own pictorial memory.

The main elements of the composition are transposed to a panel using line, texture, shading and form. Traditionally, fine drawing pens loaded with india ink are used for transferring the linear, graphical part of the drawing but I have recently been experimenting with using a silverpoint stylus for my underdrawing. The final result is softer, warmer and subtler than india ink (see the grey tones). However, that descriptive subtlety is often lost in the intervening layers of paint, thus, I have begun augmenting the silver point with india ink in order to accentuate the contrasts of the foreground. Thus, distance is described from the beginning in a few ways. The decisions made now guide many aspects of the final result, so it is important to be sure and thus avoid pentimento.

The main elements of the composition are transposed to a panel using line, texture, shading and form. Traditionally, fine drawing pens loaded with india ink are used for transferring the linear, graphical part of the drawing but I have recently been experimenting with using a silverpoint stylus for my underdrawing. The final result is softer, warmer and subtler than india ink (see the grey tones). However, that descriptive subtlety is often lost in the intervening layers of paint, thus, I have begun augmenting the silver point with india ink in order to accentuate the contrasts of the foreground. Thus, distance is described from the beginning in a few ways. The decisions made now guide many aspects of the final result, so it is important to be sure and thus avoid pentimento.

In order to minimize the amount of oil needed to achieve layers of color, I use a traditional egg tempera technique to begin the painting. Oil can be painted over egg (fat over lean), however egg cannot be painted over oil. In addition, egg tempera must be painted on a hard, firm surface, otherwise it will crack, thus the panel is prepared with a traditional gesso surface.

In order to minimize the amount of oil needed to achieve layers of color, I use a traditional egg tempera technique to begin the painting. Oil can be painted over egg (fat over lean), however egg cannot be painted over oil. In addition, egg tempera must be painted on a hard, firm surface, otherwise it will crack, thus the panel is prepared with a traditional gesso surface.

I use the egg tempera technique to indicate basic broad areas of local color. All objects at this point are better stated as pastel suggestions rather than full strong colors. In this version of the Sint Anna Kerk, I have been careful to keep my colors light in order to avoid an oversaturated painting in the middle and background areas. I have learned (the hard way) that control of hue, saturation and value are critical for describing distance. The vibrations of complimentary colors are hinted at but not yet fully explored. Also, I try to use single pigments only for spectral purity; no color mixing is done on the pallette. Colors (like certain greens and oranges) that might require mixing are indicated through separate layers of translucent paint. This layer will be dry to the touch almost immediately, but it should dry at least one week before attempting to work in oil.

Although it may seem like a sin to cover the fine egg tempera painting with a blanket of brown, the imprimatura quickly helps to establish the overall key of the piece as well as to unify any disparate elements. The previous egg tempera layer must be not only completely dried but sealed with a layer of glue size to protect it from the succeeding layers of oil based paints. The lines and colors of the previous layers continue to shine through, adding texture and interest, particularly in the mid tones and shadows. The imprimatura is a mixture of damar varnish, turpentine, and brown pigment (in this case, burnt umber). I brush it on, wait a minute or so and then wipe it off with a dry, lint free, soft clean cloth.

Although it may seem like a sin to cover the fine egg tempera painting with a blanket of brown, the imprimatura quickly helps to establish the overall key of the piece as well as to unify any disparate elements. The previous egg tempera layer must be not only completely dried but sealed with a layer of glue size to protect it from the succeeding layers of oil based paints. The lines and colors of the previous layers continue to shine through, adding texture and interest, particularly in the mid tones and shadows. The imprimatura is a mixture of damar varnish, turpentine, and brown pigment (in this case, burnt umber). I brush it on, wait a minute or so and then wipe it off with a dry, lint free, soft clean cloth.

Since I was very interested to retain the purity of the whites in the highlight areas of the picture, I went back into the fresh imprimatura with a brush dipped in fresh turpentine to remove the brown tint from the highlight areas. My theory/concept is that even though I will be painting over these areas in white oil paint to create mass and to soften edges, whatever is underneath ultimately does matter. If I want to somehow simulate the intensity of pure light – even if it is reflective and not transmissive – then the purity of the original gessoed board is important. I let the imprimatura then dry a day or so, and begin painting in the Mixed Technique.

I squeeze a quantity of cadmium yellow onto the pallette and dip a thin, wide bristle brush into the clear medium (1 part Damar, 1 part Stand Oil, 1 part Turps), then scumble in a very thin coat of yellow over the whole surfce. It sets for a minute or so and then I wipe it back off with a soft, lint free cloth. The idea is to leave some translucent color tint with some tack and work the first levels of oil back into it. Because it’s a panel and not canvas, the tackiness of the oil/varnish medium catches the brush stroke well, functioning like the weave of a canvas in attracting the brushstroke yet leaving no trace of a fabric-like texture.

I squeeze a quantity of cadmium yellow onto the pallette and dip a thin, wide bristle brush into the clear medium (1 part Damar, 1 part Stand Oil, 1 part Turps), then scumble in a very thin coat of yellow over the whole surfce. It sets for a minute or so and then I wipe it back off with a soft, lint free cloth. The idea is to leave some translucent color tint with some tack and work the first levels of oil back into it. Because it’s a panel and not canvas, the tackiness of the oil/varnish medium catches the brush stroke well, functioning like the weave of a canvas in attracting the brushstroke yet leaving no trace of a fabric-like texture.

At this stage, I work with two basic colors, yellow and gray. I mix up a gray to match the same value of the pure cadmium yellow medium, in order to set the overall darkest value. I then mix up a series of tints (5 or 6 steps) from both the gray and the yellow to white. I begin painting in large areas trying to quickly cover the whole painting with one of these tints, using a thick bristle brush and an emulsion for the pigments (1 methyl cellulose glue, .5 oil/.5 varnish, 1 water) which hastens the drying time. The drawing and egg tempera levels have already set the stage, so to speak, and function not only as guides but also as mirror like reflections. It takes only a few strokes to bring out a form. I use a fan shaped dry brush to merge forms together.

It’s fine to be working with a limited palette now, thinking ahead by laying in a more saturated yellow for both the greens and the oranges. I use the gray for neutral tonalities, shadow and to suggest distance. The overall contrast is quite low.

I squeeze a small amount of a cool, translucent red pigment out onto a pallette board. In this case I use crimson lake, in the past I have used alizarin crimson. Dipping a wide, flat bristle brush into clear medium (1T,1D,1SO) and then into the pigment, I proceed to scumble a thin layer of translucent red over the entire piece. After a minute or so, I wipe this off with a clean soft cloth, taking off as much pigmented medium as possible. The remaining surface has a slight tack to the touch.

I squeeze a small amount of a cool, translucent red pigment out onto a pallette board. In this case I use crimson lake, in the past I have used alizarin crimson. Dipping a wide, flat bristle brush into clear medium (1T,1D,1SO) and then into the pigment, I proceed to scumble a thin layer of translucent red over the entire piece. After a minute or so, I wipe this off with a clean soft cloth, taking off as much pigmented medium as possible. The remaining surface has a slight tack to the touch.

I mix up three colors this time. Red, in a series of tints up to white. Warm gray mixed in a series of tints up to white and yellow, mixed in the same way. (The value of the pure red is the same value as the pure warm gray, both being close to a pure medium gray value.) Using a big bristle brush and emulsion, I work quickly to re-establish all the values and colors of the intended piece. Occassionally I need to mix a color that requires a combination of two of the premixed tints.

But look, some strong greens are emerging although I haven’t used any green or blue pigment yet! It’s only yellow refracting back through levels of drawing, egg tempera, imprimatura and glaze. Because I use an emulsion (1 methyl cellulose glue, .5 oil/.5 varnish, 1 water) as my painting medium, the work dries quickly, the colors maintain a level of transparency, and the layers of paint are rather lean.

This is the blue level. I premix my intended colors: yellow in a series of 5-6 tints up to white, red, blue and Payne’s gray all mixed in the same way. There are about 20 little blobs of paint, which I may or may not use but I want to be able to work quickly and precisely in my choices.

This is the blue level. I premix my intended colors: yellow in a series of 5-6 tints up to white, red, blue and Payne’s gray all mixed in the same way. There are about 20 little blobs of paint, which I may or may not use but I want to be able to work quickly and precisely in my choices.

I squeeze out a small amount of pure cyan (Thalo Blue) and dip my brush in clear medium (1T, 1V, 1 SO). Cyan is a highly saturated pigment with strong tinting power so a little goes a long way. I scumble it on and after a few moments wipe it back off, leaving a slightly tacky surface that has still more blue in it than I would actually prefer. I remind myself to use Ultramarine Blue next time…

I begin to reclaim the highlights and quarter tones, working with a big brush for starters. Any color I paint now picks up a bit of blue from the glaze. Hmmm…that’s good and it unifies the painting, but is there too much blue? A lot of unexpected colors start to happen. OK, let them emerge. I need to reintroduce the main color contrasts, like the orange for the clay tile roof, the brown bricks and the green vegetation. After the main value and hue statements are set, a few details are reintroduced with a smaller brush to help refine those shapes: window and trim, shadows and highlights. After a few hours, I’ve covered the panel. But is it done?

After the blue session, all the color statements have been made and I’m happy, sort of, but there remains a bluish tint to the whole piece. I could leave it that way, but the intended gray of the church steeple and road pavement encourage me to attempt some gray balance adjustment. So, I cover the entire piece with a clear glaze of medium and wipe it back off (as usual). I mix up a series of tints using Payne’s gray this time as it is both darker and more neutral than the lighter warm gray pigment I have been using. I squeeze out lead white but mix it 50/50 with titanium white; since the painting is moving into it’s oilier stages. I strengthen the pure whites, the gray steeple and pavement, even scumble some body back into the buildings on the shadow side of the street. I put a glaze of yellow on the buildings on the left for local color, and add the final highlights to the tree. There is not much to do, but what is done crisps up value contrasts and defines gray balance.

After the blue session, all the color statements have been made and I’m happy, sort of, but there remains a bluish tint to the whole piece. I could leave it that way, but the intended gray of the church steeple and road pavement encourage me to attempt some gray balance adjustment. So, I cover the entire piece with a clear glaze of medium and wipe it back off (as usual). I mix up a series of tints using Payne’s gray this time as it is both darker and more neutral than the lighter warm gray pigment I have been using. I squeeze out lead white but mix it 50/50 with titanium white; since the painting is moving into it’s oilier stages. I strengthen the pure whites, the gray steeple and pavement, even scumble some body back into the buildings on the shadow side of the street. I put a glaze of yellow on the buildings on the left for local color, and add the final highlights to the tree. There is not much to do, but what is done crisps up value contrasts and defines gray balance.

Eh, voila. C’est fini! The cherries on top are the final touches of gold to the church steeple.

Oils

May 26, 2009

Most books advise a beginner to begin with oils as it is more forgiving. It is easier to correct a mistake for example, than with watercolor. That may be true – especially if one uses opaque pigments – but oils, by nature of the medium itself, are viscously translucent, thus understanding their innate capacity to transmit light through a clear film is ultimately critical for both succesful manipulations of form without pentimento as well as transmission of light. Eastlake noted, in referring to Jan Van Eyck, “The leading attribute of the material of oil painting, as distinguished from those of tempera and fresco, viz. its power to transmit light of an internal surface through superimposed substances more or less diaphanous…”.

There are two main approaches to painting in oils, alla prima and indirect. Although much art is created as a mixture of the two approaches, in themselves they are distinct. The contemporary art world relies quite heavily upon directly percieved and expressed imagery, thus an “alla prima” approach is emphasized. Information on the indirect methods of painting is out of style, so you have to search for it. More and more sites, blogs and forums continue to pop up on the internet. Here is one site I have found that is a fine, yet relatively dis-interested treasure trove. There are others.

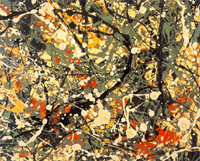

Jackson Pollock Abstract Expressionism

Alla prima essentially means executed in one session as exemplified by Jackson Pollock in his drip paintings. There can be no argument against this method of approach as both its demands and results can be superlative. After all, if a painting has any chance of reflecting the evanescent truth of the moment, it needs to be created in the same spirit, with a Zen-like accuracy and intensity.

the Mona Lisa

What then are the values or possibilities of a more indirect technique? Does a laborious technique result in a tedious and heavy painting (it often does!)? Can a painting developed indirectly still retain the freshness of the moment? If so, then how? Thus, for those who feel themselves drawn to an indirect method, the knowledge of ancient techniques is extremely helpful. Indirect painting simply means developing an image through a series of manipulations over time and calculated to achieve a particular result. A further refinement of the indirect painting technique is the mixed technique. Both allow for a methodological layering which in itself creates optical effects of great beauty and luminescence. Subject matter aside – what can be more eternal than that?

Encaustic

May 26, 2009

Encaustic:

portrait in encaustic

Interestingly, encaustic or hot wax painting, was known to be one of the major creative techniques used by the ancient Greeks. The Egyptian tomb portraits, which are some of the finest examples of encaustic portrait painting available today, were (according to Ralph Mayer) done by Greeks (not Egyptians). In recent times Jasper Johns has used the technique with a great deal of success in his series of images of the American flag. It is a technique that traditionally requires alot of cumbersome tools. Today the process has been streamlined with simpler tools but for purity, simplicity, and honesty’s sake I will try to describe the technique that I have used.

The Ground:

The Greeks reportedly used encaustic on walls and panels. A revival of the technique in the 18th/19th century concentrated mostly on mural painting – with reportedly insubstantial results, now 200 years later. My own experience has been entirely on wooden panels, prepared with traditional chalk gesso (the same treatment that is used for egg tempera).

Tools:

As the medium is melted beeswax, the first tool one needs is a pallette for mixing the colors in a molten state. Years ago, I went to my local metal junk yard and commissioned a pallette measuring 18″ x 28″ of 1/4″ steel plate welded on four sides by legs 5″ high (also of 1/4″ steel plate). This pallette then sat on top of a hot plate with an air space of approximately 2″. At the time, I remember it cost me about $10. The second tool one needs is a hotplate. The best are the kind that allow for variable temperature adjustments. A quick search at the local flea market should offer what you need.

Materials:

The same dry pigments that can be used for egg tempera can be used in encaustic. Purchase a few blocks of fine beesawax. Melt some wax and mix it with approximately 20% damar varnish crystals by volume. Mix this molten fluid together with a similar amount of dry pigment and keep it in a metal cup on the warmed pallette. Mix up a few colours as needed for the project at hand and keep them warm on the pallette. These days encaustic sticks can be purchased with the resin/oil component already mixed in. Your choice.

encaustic flag by Jasper Johns

Painting:

Molten colors can be applied using bristle brushes or even the pallette knife. As the paint hardens almost immediately upon contact with the panel, expect a highly textured, immovable result. [My original experiments were done outside in the hot humid summertime, so setting time worked slightly to my advantage.]

Burning In:

Further manipulations can be obtained by heating the panel surface with a heat lamp. Be careful to keep the surface horizontal to avoid runs. The final “burning in” is also done with a heat lamp close and evenly rotated over the surface to achieve a final fused result. In this way heavy impasto effects can melt into thin, veil like veneers.

There are some other resources for encaustic. The University of Delaware’s MITRA forum is an invaluable reference for artists on all things technical. Notebook is another. These days there are many blogs dedicated to the arts and crafts practice of encaustic. They can provide useful tips and tricks but, of course, it’s best to always do your own research by consulting tried and true technical manuals, like Reed Kay’s, The Painters Guide to Studio Methods and Materials. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1983.

Egg Tempera

May 25, 2009

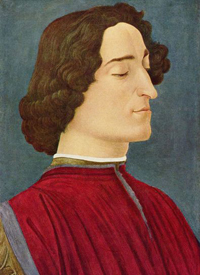

Egg tempera Medici Portrait by Botticelli

Egg tempera is an time tested technique, especially well loved by panel and icon painters. It renders flat graphical shapes and fine precise detail quite well. Softer gradual modulations are possible but take practice and patience. The unvarnished final work has an almost chalk-like finish to it. This technique formed the backbone-skill to any medieval or renaissance painter’s tool chest. The twentieth century has witnessed its revival with Andrew Wyeth being perhaps its most famous spokesman.

For anyone wishing to ask experts geeky questions about the medium check out the MITRA forum. In the past there has also been the Society of Tempera Painters (whose informative forum is currently offline). The Tempera Society had a well established site and forum, documenting many aspects of the process as well as related techniques. In its absence, I’d suggest picking up a good book and starting in. The online version of Daniel Thompson’s, The Practice of Tempera Painting is one of the most extensive sources around. Cennini is charming even if a bit antiquated in his terminology and procedures. If you are looking for something more general in order to get started, try Ralph Mayer’s “The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques”, Reed Kay’s “The Painter’s Guide to Studio Methods and Materials”, or “The Materials of the Artist and Their Use in Painting” by Max Doerner. All are tried and true comprehensive source books for the craft of painting.

Egg tempera is a paint made from an emulsion of oil and water. The final paint film is not as flexible as oil. Thus, to avoid cracking, the painting is executed on a firm and stable panel not on a stretched canvas. At the moment, I use egg tempera primarily as an underpainting. The links here on the right offer some info – by no means extensive – about how I prepare my gesso and panels.

Pigments:

Be sure to supply yourself with a good collection of dry pigments – avoiding poisonous materials whenever possible. You don’t want to breathe in toxic dust. By grinding your own paints you get to know the specific characteristics of each pigment – opacity/translucency, saturation, hydrophobic or philic, chromatic nuance. Online suppliers are very helpful if you do not live in a large city with a big art supply store. Get a thick piece of frosted plate glass and a glass muller. Otherwise a pallette knife and wooden painter’s pallette can suffice in a pinch. Grind up a small amount of each pigment you want to use in distilled water, making a smooth paste. The pastes can be stored in plastic film containers for short periods without drying out. To extend that drying out time I usually insert a piece of sponge at the top of the jar. Keeping it moist prolongs the life of the pigment paste.

The Egg:

Locate as fresh an organic an egg as you can. Crack the shell carefully in half without breaking the yolk. Carefully move the yolk between shell halves to isolate the yolk from the white (all the while protecting the egg yolk membrane from puncture). Let the white albumen drip away. Pass the yolk back and forth between the palms of the hands in order to dry it off. Roll it across a piece of absorbent paper towel for further drying. Eventually you should be able to pick up the yolk by it’s sac. Hold it over a small clean jar (empty jelly jars from hotels are great for this) and pinch the bottom. The pure yolk will drip out. Add an equal amount of distillled water, cap, and shake it. Store in the refridgerator.

Tempering the Paint:

On your glass palette add equal amounts of pigment paste and egg yolk. I use a palette knife to measure a “bean” of pigment paste and a small pipette to measure the same by dipping into my prepared egg. Mix until smooth. If you have already ground up your pigments in distilled water, then adding the egg binder now is easier and requires much less grinding. Some pigments will require more yolk, others less. To make sure you have tempered your paint correctly, Take a moistened sable brush, dip it in your newly mixed paint and lay a stroke on a nearby piece of window glass. It should dry quite quickly. Then take a one-sided razor blade and gently scrape the paint swash off. It should maintain its own consistency and curl off like a ribbon. If you have not added enough egg the pigment will return to powder and flake off. If you have added too much egg the paint film will lack chromatic saturation. Let experience be your guide. Soon you will get the knack of it.

When you are satisfied that you have tempered your paint correctly, transfer this mixture to a painting cup. I use a nested set of porcelain dishes that have a top cover. The tempered paint is rather thick, too think for painting, so at this point it is important to add additional water in order to arrive at the right mixture of pigment/yolk. How much water? Apparently, that doesn’t really matter. If your paint has been tempered correctly you can (if you wish) dilute it with large amounts of water so as to paint with many fine watercolor-like washes. As you work, it may seem as though the color is not building, but be patient and you will see that it does.

Painting:

Sable brushes dipped in this watered down paint will be too saturated for the painting stroke. Using your thumb and forefinger press the excess liquid out until the brush renders a clean full stroke without leaving behind a blob of paint at the end of the motion.

Egg tempera does well with many light thin strokes. Do not immediately rebrush a stroke. Let it dry, then add another level. Because it dries so quickly this is usually not a problem at all. In this way soft transitions can be achieved. But is is important to let your brush dance over your whole painting. Do not obsess in any one area, if it has not thoroughly dried it can become overworked and lift off earlier levels of paint, creating a hole that is difficult to repair. Stay light and playful, attentive to the whole work. Each artist decides how to use this medium to his/her own ends.

Fresco

May 20, 2009

fresco from the Sistine Chapel

Historically, fresco was used to decorate large interior spaces – often in churches. The Sistine Chapel remains as one of humanity’s great treasures executed in this technique. In the 20th century during the great depression, the WPA sponsored many public works in fresco which yet survive today. Working in fresco is very coarse, simple and elemental. The paint is applied directly upon fresh plaster. The chemical changes that occur as plaster sets lock the pigment into the surface. There is no eraser. Small mistakes may be able to be handled in fresco secco (no guarantee). Larger mistakes simply require a fresh start.

The information here does not come from long, in depth experience, rather this is what I know from a few experiments. If you are serious and interested, I recommed a good book, course, or seminar. Notebook is an informative disinterested site with more information as well as additional links. This site from Sister Lucia Wiley a (deceased) WPA fresco artist is quite informative and helpful. If you do not have a wall handy on which to experiment, the back side of large tiles from your local tile shop may offer a highly textured surface fully appropriate for your first fresco experiments.

Arrichio:

A wall that is ready for a mural must be of relatively even surface but coarsely textured. It must be solid and not allow moisture to enter from the rear. It is a good idea to wet the entire wall surface with a hose the night before applying the arrichio in order to insure a good bond. The arrichio is a mixture of slaked lime and sand (1 part lime putty to 2-3 parts coarse sand), applied about 1/2″ thick. It can hold the basics of the underpainting. If you are painting on tiles, you can omit this step and go straight to the intonacco.

Sinopia:

The full scale design or drawing can be transferred to the arrichio. The Renaissance Masters seem to have used red sinopa pigment for laying in the basics of the design. It will be covered by a final layer of plaster called the intonocco, so the purpose is to lay in the complete composition to determine relationships in situ, as well as provide a guide for the ‘giornata’.

Intonacco:

This is the final layer of plaster upon which one paints. It is a mixture of slaked lime putty, sand and powdered marble (one part lime putty to two parts fine sand plus 10% marble dust), applied approximately 1/4” thick. Be sure to wet the surface well to insure a good bond with the plaster (this is an important step in order to avoid the having plaster flake off a year or two later due to an insufficient bond). An amount of fresh plaster is mixed and plastered onto the wall (or tile) for one day’s effort (which is then called the ‘giornata’). The ‘sinopia’ (or design that has been laid on the arricio) is used as a guide to determine where to lay in the ‘giornata’. Artifical boundaries (like the traditional grid for transposition) are avoided, whereas edges of bodies, buildings etc..form natural boundaries. The working session for one day of fresh plaster can at best be 12 – 14 hours (depending on your external climate). Therefore, the design needs to be well thought out ahead of time in order to be able to complete the day’s section well and to allow it to invisibly merge with the rest of the painting. The color of the fresh paint may not exactly match that of the dried, so at least be sure that your pigment mixes are the same, then the dried painting will be fine. Allow about an hour for the fresh plaster to set before beginning to paint.

Cartoon:

If there is no sinopia, a monochromatic design rendered full scale for the project, is then transferred to the fresh plaster intonocco via a pounce bag tapped over tiny holes that have been pricked into the drawing. This can help one to work quickly and effectively. Be careful, the pricked holes become part of the final painting, so only transfer dark lines, or use a light to medium value pigment in your pounce.

Pallette:

Because the action of setting the pigment occurs as a chemical change within the plaster, the pigments need to be chosen carefully. Stick with known minerals from the earth as the lime burns organic and vegetable pigments. See the seperate page for fresco pallette recommendations. Using a pallette knife, simply mix a small amount of dry pigment with distilled water to create a useable paint.

Painting:

fresco WPA of Fisherman's Wharf

Now, finally, to painting. A tip on technique: as in watercolor, many dilute strokes can be absorpbed to build up color. In this way one can avoid large garish mistakes while gently building up the design. This of course, needs to be balanced with the need to work quickly. Remember to let an area dry before returning to it to apply fresh paint. Have on hand a variety of sizes of good sable brushes. Mix up your colors and tints before hand. Good luck. Have fun.

If you run out of time, or find small errors that need correcting, it is possible to continue in Fresco Secco after the plaster has dried.

the Oil Pallette

May 20, 2009

I suspect that every artist has his or her favorite pigments and colors. It is necessary to find your own. It can be quite challenging at first to sort one’s way through the huge selection of colors available at any art supply store. Experience is the best guide. But that’s hard when you don’t have it.

Here’s what I use:

Color

- Two yellows (a cool and a warm one, like citron yellow and cadmium yellow medium)

- Two reds (a cool and a warm one, like alizarin crimson and cadmium red medium)

- Two blues (a cool and a warm one, like thalo blue and ultramarine blue)

The Earth Colors

- Sienna (burnt and raw, though I most use burnt)

- Umber (burnt and raw, though I mostly use raw)

- Mars Red (a red iron oxide)

- Yellow Ochre

Neutrals

- Two whites (Lead white and Titanium)

- Warm gray

- Mars black

From these basic colors I can mix just about any thing I need while maintaining a clear idea of how I got there. In addition, the spectral purity of a color can best be appreciated by employing it directly out of the tube, unmixed. Therefore, one can try to achieve certain ‘mixed’ colors through translucent layers of paint, rather than mixing on the pallette. Doing this means becoming familiar with the characteristics of the pigments themselves (opacity/translucency, saturation/tinting power and capacity to absorb oil). It also means using the translucency effects of the oil medium to create rich vibrant colors, that resonate like a sunset.