The non-duality of self-expression

March 30, 2010

Self-expression as unitive consciousness

I recently completed the translation of a piece of text based upon the drig-drishya-viveka from the Indian Advaita Vedanta tradition. The thrust of that classical text is that the fundamental unity of being-awareness, previous to all conditions, is discovered by continually stepping backwards through each level of phenomenal conditioning to always discover the unifying quality of being-awareness on the preceding level. Its non-dual premise got me thinking about painting – and all the arts for that matter – as experiential examples of that unitive quality of consciousness manifesting itself through transparent action on varying levels of material existence.

To flesh that statement out, I can try to clarify what I now understand to be a main aesthetic principle. What makes a piece of art – art – is its own vibrant inner unity as the expression of an idea, feeling, sensation, movement or combination thereof. It’s not about – and never has been – a good, even excellent, depiction of some external reality. But rather it is about the consciousness-unity of the artist (subject) merging with his or her materials and subject matter (object) in such a way so as to reflect back a little piece of cohesive life to the consciousness-unity of his or her viewers. When it’s good, it’s magical. As viewer, or listener, we enter into the world of the artist, we recognize some aspect of ourselves and are transformed by the experience.

Additionally, and at this point in humanity’s knowledge of itself, it’s certainly not required that the final form of a piece of artwork be classically realistic. Most contemporary artists prefer at least some level of abstraction. But modality aside, what makes a work of art eloquent is the unity of the intent expressed through the materials on into the final form. “Perfect”, we say: form = function, function = form, in an aesthetic sense. The only rule is that a piece of art must be true to itself, whatever that self is. Looking at artistic creation from this point of view frees both the artist and his or her audience from any formal constraint, allowing modality, medium and message to merge by simply remaining true to the original impulse.

Self-expression of the multi-dimensional Self

I’d guess that most artists in their creative act intend to hint at what they experience as ineffable. If they could say what they wanted to say with words, they would do it, but shapes and images, music or dance often speak more eloquently to and from a level that is non-verbal. For the artist, in the visceral interplay between sensation, perception and action, a creative discipline is chosen which resonates with their sensibilities, whatever they may be. Additionally, to the extent that artistic expression can be seen as a response to the interaction of self and world, that response is best recognized as arising from the entire gamut of human experience. So there is a response of and to the self/world experience of waking state consciousness, dream state consciousness and deep sleep or meditative consciousness. Artists who attempt to explore and express their response to these different dimensions of human experience find themselves choosing a visual vocabulary which resonates accordingly, be it realistic, symbolic or abstract. Thus, at least within the visual arts, there seems to be a relationship between the experience of self-world and the choice of a particular creative modality. What’s that relationship? Let’s take a look.

Realism

Realism offers the artist a visual vocabulary for exploring the objects which daily present themselves to the senses within the waking state of consciousness. It’s an exploration and discovery of the phenomenal world surrounding an individual who essentially considers himself/herself as separate from these external objects or forces. For most people in the Western world, the contents of the waking state of consciousness constitutes their sense of “reality”. When realism is most successful, the artist is able to both intensely experience and viscerally convey a sense of inner unity with these external objects or forces, thereby offering others a chance to experience their own reality in an enhanced way.

Take, for example, the high level of realism in a powerful work by Da Vinci, Rembrandt or even Van Gogh. A recognizable external reality is certainly depicted, but it’s charged with an inner unity, often radiating with great intensity. Much of the history of Western art – at least previous to the twentieth century – has spoken this language. Psychologically speaking, such work can reflect a personality in varying modes of relationship to the surrounding phenomenal world, a world furnished with the forms perceived within the waking state of consciousness. Its realistic depictions can range from polished, to symbolic, to naïvely abstract: the best works containing a mixture of all three.

Symbolism

In contrast, symbolism as a methodology offers the artist carte blanche for the exploration of his or her own dream-world consciousness. Graphically speaking, there is usually a simplification or reduction of external objects to their inner essence. For the artist, it’s a rediscovery and expression of personally significant images or forces arising from within their own consciousness. The symbolist then, no longer sees themselves as completely distinct and separate from the formerly external objects of waking consciousness, but rather understands themselves to both contain and manipulate – or even be manipulated by – these projections. The artist’s sense of self expands through exploration of this dimension, just as humanity’s knowledge of itself also expands through a recognition of archetypal myths and characters. This expansion carries with it a sense of inner veracity, a greater self knowledge, a knowledge that includes and expands upon the reality of the waking state. Thus, when this mode of creative expression is most successful, the artist is able to recognize this level of being-experience within themselves and viscerally convey its (often archetypal) contents to others, offering the viewer a chance to perceive themselves and so their own reality in a new and expanded way.

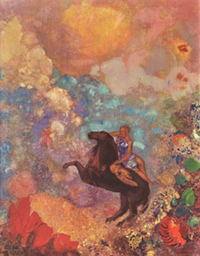

Consider, for example, the mythic gods and heroes of Jung’s Red Book, the dream world of lucid imagination à la Odilon Redon, the powerful haunting entities of Dali’s surrealistic almost shamanistic inner journeys, or Picasso’s African masks. These are powerful images evoking associations to sub-conscious human experience-memory. Psychologically speaking, such imagery resonates on the level of the unconscious mind – both individual and collective. The end of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century, in particular, celebrated this kind of visual vocabulary in Cubism, Fauvism, Symbolism, Primitivism, Surrealism and Expressionism, although, of course, the art of indigenous cultures has always contained such imagery.

Abstraction

Contrary to the two previous modes, abstraction opens the doorway towards that realm of being-experience which extends far beyond the sphere of a separately existing person within the world of external forms. The artist uses this mode as an attempt to get to the absolute essence of experiential forms by questioning his or hers (and so also the viewer’s) own sense of reality. It delves into the expansively open space of the deep sleep or meditative consciousness where no “person” exists. For subject matter, there is none, not really, but rather the structures of perception and/or the medium itself are explored or examined in an open, intimate and often playful manner. When it’s successful, the artist is able to recognize this level of being-experience within themselves and reflect back its lack of phenomenal content with an economy of means. Perhaps that is why abstraction as a form is both so difficult yet sublime, so condensed yet expansive, so negating yet fulfilling – and ultimately so unapproachable by the rational mind.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, through Abstract Expressionism, Color-Field, Minimalism, Hard Edge, Lyrical Abstraction and others, the demolition of graphically meaningful forms moved ever further towards abstraction. The artist’s intent focused on a visual vocabulary speaking for and to the ineffable non-phenomenal world, always, already present within a human being, and assumed that by avoiding representational elements altogether, the artist could more effectively suggest the sub-symbolic level of being-existence. There have been a number of artists visually evoking this level, Mark Rothko being one of my own personal favorites. Pure abstraction, then, as a psychological projection of no-self portraiture, transcends traditional Western psychology and moves into the supra-personal spiritual world of Yoga psychology. This expansion carries with it the potentiality of ever greater inner veracity, ever greater self knowledge, a knowledge which precedes and so both includes and expands upon the realities of the dream and waking states of consciousness. It is exemplified by the deep, dreamless sleep state of consciousness (turiya) or the deep, peaceful calm of a meditative state.

Self-expression as self-projection and self-perception

An alternate way to approach (a non-dual) understanding of creativity is through exploring the subject/subject matter/medium dialectic of creative expression. We can take the creative act as a dialectical exchange of these three entities. Accordingly, the subject matter of what an artist creates is often an intimate projection of their own self-image, whatever form that image may take at any particular time. Who am I? is expressed on different levels of being-experience. Through the projective objectification of some aspect of themselves the artist turns around and says “Yes, that’s me”. Yet simultaneously, through that same act of creative objectification, it’s also abundantly clear “No, of course, that’s not me”. A similar dialectic of self inquiry is documented within the drig-drishya-viveka: recognizing, aligning with, then finally negating, any particular objectified aspect of self-perception by affirming the pre-existing nature of the unifying awareness which perceives it.

Accordingly, the realistic painter feels themselves especially drawn to particular people, landscapes or objects and uses his or her tools to both explore and express the sense of intimacy or lack of separation he or she feels for these external forms. This self-projection tends to move towards symbolism when, through insight, the inner significance of these external forms becomes recognized. Then the subtler symbolic meanings acquire a stronger sense of reality than the external forms themselves, both including and expanding the artist’s (as well as the viewer’s) sense of self.

This process progresses as the artist attempts to discover the absolute essence of external forms and in so doing digs ever deeper into themselves, experiencing the accompanying sense of inner veracity like a guidepost. This probing has a tendency to lead towards abstraction. When the mind alone pursues this direction to its logical aesthetic conclusion it pronounces, “Form is dead”. How true. But what has actually happened is only this: mind has discovered its own limits, just as, through self inquiry the limiting constrictions of the “person” become fully recognized, allowing these relative structures to finally dissolve and die. Form is dead, but the one who recognizes that fact cannot be. Similarly, within artistic activity, the irreducible effervescence of creativity itself does not die and it never will. Experience tells us so.

Unity consciousness as the creative act

The final answer is this: nothing is. All is a momentary appearance in the field of the universal consciousness. Continuity as name and form is a mental formation only, easy to dispel.

– Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj [pg. 415, I Am That]

Ah ha! The ultimate discovery, in art, as in life, there is no absolute object which can be pointed to, no thing which can be specified, no person to be delineated. Rather there is a living, vibrant, ineffable consciousness which has the particular characteristic of spontaneously, joyfully, irreducibly, creating multiplicity from unity and – at least within human consciousness – of creating unity from multiplicity. Whether the style of that unified form is realistic, symbolic or abstract begs the question.

The 21st century art world has historians scrambling to find an “ism” for the art world of today. There is no definitive style. Anything goes. What’s up for the future is anyone’s guess. Yet for the 21st century artist, if, after tossing realism out the window as passé and spending decades analyzing the symbolic content of their own internal dream-world, or alternatively sitting on a mountain peak in meditative abstraction, if then there is not a humbled, yet enlightened return to the daily marketplace of non-dualistic realism, personally, I’d be surprised. As human beings we exist in an integrated way within all three states of consciousness. As such, they inform and interpenetrate one another. Deprivation of any one for a length of time produces an unhealthy imbalance. So, I’m betting on an integrated approach to creativity, one in which the realistic, symbolic and abstract levels of the visual vocabulary will all be transparently operating. What will that look like? Who knows, but won’t it be fun to find out? And isn’t that simply one way to look at what is already happening, swirling all around us?

The 21st century art world has historians scrambling to find an “ism” for the art world of today. There is no definitive style. Anything goes. What’s up for the future is anyone’s guess. Yet for the 21st century artist, if, after tossing realism out the window as passé and spending decades analyzing the symbolic content of their own internal dream-world, or alternatively sitting on a mountain peak in meditative abstraction, if then there is not a humbled, yet enlightened return to the daily marketplace of non-dualistic realism, personally, I’d be surprised. As human beings we exist in an integrated way within all three states of consciousness. As such, they inform and interpenetrate one another. Deprivation of any one for a length of time produces an unhealthy imbalance. So, I’m betting on an integrated approach to creativity, one in which the realistic, symbolic and abstract levels of the visual vocabulary will all be transparently operating. What will that look like? Who knows, but won’t it be fun to find out? And isn’t that simply one way to look at what is already happening, swirling all around us?

about Giclée or digital printing

January 29, 2010

With the advent of the digital revolution, the “giclée” or digitally produced ink-jet art print is an upscale and promising venue of digital imaging technology. Images can be easily created, shared and printed the world over. It is clear that inks, paper and techology will consistently improve to offer high resolution, archival prints which can qualitatively equal or even surpass traditional lithography for only a fraction of the cost. As a new medium it promises to be an art in itself, because the tools are back in the hands of the artist.

But as a new medium, it is also important to distinguish a few basic elements of the larger printing world to which it belongs. Printing, be it digital or lithographic, occurs in the world of CMYK, or subtractive light and refers to multiple identical reproductions. It is to be differentiated from the world of painting which usually (but not always) occurs in the world of subtractive light and whose pallette is greatly expanded beyond four basic colors. Additionally, the act of painting refers to a unique product.

What can be confusing for consumers/collectors is the term “limited edition print”. Traditionally this term referred to a run of prints which were created from a means that became dissipated through the action of printing. For example, etching plates whose fine lines grew softer after repeated use. More often, the term “limited edition print” simply referred to the amount of prints generated at any one particular time for economic reasons, not necessarily technical.

In the current world of printing, whether lithographic or digital, the term “limited edition print” refers to economic factors and not physical dissipation, that is the number of copies generated at any one time is determined by how much the artist can spend to produce the images he/she hopes to sell rather than the dissipation of digital pixels (which is absurd) or lithographic plates, which do in fact dissipate in extremely large runs.

In this regard, the Giclée print is directly advantageous to the artist: no huge lithographic print run to manage, pay for and inventory. Artists can now “print on demand” and even sign their work, completely bypassing the “limited edition print” run event, potentially rendering the term altogether meaningless (buyer beware).

Technically, the Giclée print may also be superior to traditional lithography since the ink jets do not require the intervention of tiny lithographic dots to hold the ink. Finer gradations and subtler details can be rendered. For example, the current top range digital printers includes two levels of jets for the cyan and magenta inks (one for the normal range of values and one particularly sensitized to reproduce highlight detail). The archival qualities of the inks are consistently being improved (but still do not retain the longevity of a well executed oil painting) while the substrate is whatever quality technology or ecomomics allow.

The drawback of the Giclée print is the same as it ever was for lithography: CMYK cannot reproduce certain secondary colors, as well as even certain pigments of yellow, red and blue; what is visible on the LED monitor in RGB may not be reproducible in CMYK. Additionally, importantly, and in contrast to painting, a print surface offers extremely little refraction of light through its micro millimetered surface-depth. So the play of light through its surface remains predictably (mechanically) stable, unlike the subtle differences that can be experienced when viewing an original painting. So although the Giclée or digiprint offers many possibilities, a print is still a print…

More Musings on Memory

July 27, 2009

Two important events occurred in mid-nineteenth century France: Louis Daguerre’s patent application to the French Academy of Sciences for his Daguerreotype and Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran’s publication of a systematic way for the artist to develop visual memory. The former was destined to radically change the way humans communicate, while the latter would eventually become relegated to the now old fashioned practice of perceiving, conceiving and rendering external reality in terms of three dimensional forms. Additionally, the former could (after the additional technological advancements of more than a century) be used by anyone to communicate anything, while the latter took years of practice to master (by fewer and fewer artists). In Lecoq’s time, one could imagine him to be deeply aware of how the early stirrings of photography might impact both the world – and the artist. But also, the world of his time was still deeply embedded in Western Civilization’s long tradition of the representation of classical forms of beauty. If we fast forward more than one hundred and fifty years, we can see a remarkably different art world functioning now and understand why he has hardly been heard of. Still, back in the day, his methods had a strong influence on Fantin-Latour, Legros, Rodin, Lepère, Lhermitte, George Innes and James MacNeill Whistler, among others.

One additional factor – which also occurred in France around that same time period – could have been nail in Lecoq’s memorial coffin. One year after the 1862 publication of Lecoq’s revised edition of L’Education de la mémoire pittoresque was the famous 1863 Salon des Refusés. Art history books mark this as the beginnings of the Impressionistic movement. It’s readily acknowledged then that the advent of photography provided the impetus for Impressionism and the further deconstruction of the realistic picture space: Neo-Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism, Da-Da, Expressionism, Pop-Art, Hard-Edge, Color Field, Minimalism, Symbolism, etc… . As they all continued to move away from a form oriented, realistic rendering of external reality they moved towards an abstract vision of an inner, subjective reality. This inner subjective experience of consciousness (on whatever level) then became objectified using whatever tools might be available to the artist – or to which they were attracted. Such expressions then need not have any relation to the external “objective” world rather, if successful, these expressions somehow depicted a universality (that is not subject to the subject-object dichotomy of both science and even language itself). So I wouldn’t argue against any of these developments, as a young artist I was exposed to them all and truly appreciated most. Yet also as an artist I do question what has been lost in the interim. For example, my own artistic education included very little formal training, that is, training in the rendering of form and the use of the traditional materials to do so. So I’ve really had to teach myself.

At this point, and as a very generalised statement of the current artistic world, I humbly submit that by losing touch with the various tools and techniques which artists have used for centuries to render personally significant reactions to the external world in and around themselves, humanity has lost an essential relationship. An essential mirror. I certainly do not argue against abstraction, and conversely, I do not argue for realism. Both languages can be exceptionally powerful or exceptionally vapid, depending upon their practitioner/spokesperson. I’m just arguing for integration. The physical absorbed into the metaphysical; the metaphysical rendered meaningful through the physical. The Heart Sutra of Mahayana Buddhism expresses it this way: Form is Emptiness and Emptiness is Form.

Development of Visual Memory in the Arts

July 23, 2009

In 1848 the art teacher Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran wrote a treatise called L’Education de la mémoire pittoresque for his students. That treatise was revised and republished in 1862. Later, he wrote two other small texts for his students which were published in 1876 and 1879, respectively. Many notable 19th century artists passed through his atelier: Fantin-Latour, Legros, Rodin, Lepère, Lhermitte among others. Subsequently through Legros, many other artists, like George Innes and James MacNeill Whistler were influenced by his ideas.

Although the mainstream current of twentieth century art has moved away from form inspired realistic interpretations of the world around us, the role of personally significant memory has never been greater. It is with that in mind that I have finally located, downloaded and printed out this text. The translation, which was done approximately one hundred years ago, appears to be a fine one, well researched among the still extant students of LeCoq at that time.

I’m posting this link as information for anyone else who may be interested in exploring Lecoq’s work. The Training of the Memory in Art and the Education of the Artist, Translated by L. D. Luard. Et l’original en français: L’éducation de la mémoire pittoresque, de Horace Lecoq de Boisbaudran. Yesterday, for 14 Euros and an hour of my time, I located the link, downloaded the file, burned a CD, took it to a local print shop, for the which I received a simple, black and white, plastic coated, spiral bound edition. I now have a copy of a book that I have searched twenty years for. Hooray for the internet!!!

Light and Color

May 19, 2009

To talk about color divorced from whatever medium in which it is suspended means necessarily taking a theoretical approach. So, a small digression here:

There are many ways in which both the painter and the scientist approach color. For the scientist, a rational model is constructed to categorize and describe it as a phenomena. At colorsystem.com there is an excellent presentation in German of the various scientific theories that have been created over time. Additional to scientific theories, artistic color theories tend to be more relational, more psychological, and ultimately more visceral. The theories of Josef Albers, in ‘The Interaction of Color’ and Johannes Itten, in ‘The Art of Color’ are two such 20th century examples.

Another way to approach color involves viewing it from the standpoint of light itself, that is, additive and subtractive light. Notebook has an interesting resource page on the topic of Light and its qualities. Thus, while the painter’s craft necessarily exists in the world of subtractive light, by manipulating mediums and pigments to experientially stimulate thoughts, emotions and sensations, it derives – as does life itself – from the world of additive light.

additive primaries

The primary colors for additive light are red, green and blue. Thus, if three different spotlights are focused together upon one location, and one light is covered with a filter of red, the second of green and the third blue, the location itself will reveal white light to the human eye. The technologies of television, computer screens and color separation in the printing industry are all based upon additive light theory or RGB (red, green, blue).

subtractive primaries

The primary colors of subtractractive color theory are yellow, red, and blue. Every young child learns this in kindergarden. He/she learns quickly that yellow plus red makes orange, yellow plus blue makes green, red plus blue makes purple, and all three together create black (or a very mucky brown). I call this kindergarden primary color.

process pramaries

A further refinement to subtractive color theory are the primary colors of the printing industry. Rather than the yellow, red and blue of kindergarten, the printing industry uses process yellow, magenta, cyan and black. Process yellow actually contains the slightest bit of green in it – a cool, translucent, lemon yellow. Cyan is a translucent and dark turquoise kind of blue. While magenta is a cool, translucent ruby red, similar to the external fleshy covering of pomegranate seeds. These subtractive primaries, derived from additive light theory combine in different ways – principally through layering – to create the whole gamut of visual color that we experience in 99% of our printed material.

I tend to speculate that if magazine green never comes from green ink, then why should an artist mix his or her colours so easily on the pallette? Similarly, through the luminosity of oil, a painter’s green created from superimposed layers of yellow and blue is qualitatively a different experience than that of a mixed green on the pallette. Thus, since painting occurs in the world of reflective light, and subtractive color combinations are intuitively clear, it’s reasonable to ask, how much palette mixing is truly necessary if the beauty of light itself is the goal? Additionally, any colour we perceive in the natural world is always more beautiful in the degree to which it can transmit light. The ancient techniques for creating imagery are time tested procedures for isolating, cherishing and showcasing the spectral purity and luminosity of individual pigments. The medium of oil is particularly adept at transmitting light through layers.

on Materials and Aesthetics

May 7, 2009

An excerpt from the book: Painting in reference to the raw materials and the role of technique in the creation of art by Nicolas Wacker. Published by Editions Allia, Paris, France. Translated by Ellen Trezevant.

“All spiritual creation is dependent on its material. Without it, no transmission would be possible. The mystery of art lies in this collaboration between the material with the spiritual. For it is through that, and that alone that communication can be passed. How and at what moment does matter become spirit?

In the creation of art it will always be the material and that alone which stands guard over the precious message of a work of art. It is through a thorough knowledge of the materials which one wishes to use, applying them at will, and adapting them to each case, that one comes to know the effect that finally can be achieved.”

These words of Wacker resonate so well with my own temperament that I hesitate to add anything of my own. Yet since they were originally spoken about fifty years ago, the sentiment bears a fresh look. The contemporary art world appears to function in a no-holds-barred state. All forms of expression can be called “art” if they are somehow art: realism, superrealism, photorealism, abstraction, expressionism, naieve, primitive, conceptual, assemblage, installation, video, etc… What is it that makes the world pronounce the word: ART?

Although the question is rhetorical and cannot easily be answered in words, for the artist, the magic really happens when the materials they cherish, investigate and use finally resonate to their own inner vibratory truth – whatever that truth may be. And the closer each individual artist’s truth is to that of a universal inner truth of humanity – well the greater the chances are that someone, somewhere will call it ART. Otherwise, there are fads and fashions that will go in and out of style. My two cents.