A non-dual definition of art

August 4, 2023

Art is: (in the Dutch language) een gevoelsmatig einheid. Period. The “gevoelsmatig” element refers to the channel of consciousness on which it vibrates, while the “einheid” element (which I’ve also written about here) refers to the unifying thrust inherent to the creative process as well as to its manner of perception.

Translated and expanded into English the definition becomes: a felt-intuition succinctly and evocatively expressed/communicated as a sense-based unity. It might be helpful to unpack that a little bit.

“felt-intuition”

The Dutch word, gevoelsmatig guides me here. I’ve written about that word (particularly in the context of Western philosophy) here and here. Gevoelsmatig refers to a sensitively refined, intuitive, instinct-type of feeling-knowing that is not only fundamental to all forms of art but to existence itself. It refers to an inception, a feeling-knowing which may be based on sensations, emotions, or impressions not entirely understood and so (at least to the subject, but also to others) may appear irrational. Nevertheless, it’s a subject-based channel for acquiring “knowledge”, self-knowledge. Birds know when to fly south, humans know when a relationship has ended: it’s gevoelsmatig.

In English I have chosen the compound word felt-intuition as a translation for gevoelsmatig instead of emotion or feelings. Using the word emotion especially to describe art would, I feel, be reductive because not all instances of art are transmissions of emotion. Rather most, if not all, speak to and through the senses, describing/communicating how some external or internal event felt to the artist, allowing the perceiver/receiver to experience something similar. (which is, by the way, a good example of non-duality) The word feelings too, is inadequate because it does not include the knowing aspect of the word “gevoelsmatig”, for the greatest art communicates a sense of meaning even – or especially if – that meaning is not entirely understood. Art can speak directly, viscerally and transcendentally to the person, to the transpersonal (mythic or religious imagery) or the supra-personal (abstraction) levels – or all three simultaneously (!).

“expressed/communicated”

Everyone experiences emotions and felt-intuitions. The artist tries to communicate such things through a process of objectification. The artist needs to be grounded in his or her own experience in order to communicate directly from it, extracting the essential. Still, not everyone possesses the capacity to objectify evanescent feelings or intuitions, that is, to recreate them effectively. Additionally, not everyone gives themselves permission to be in contact with their own deeper levels and to express from those spaces: cultural/upbringing factors may encourage attractive emotions which, when expressed as “art” become simply superficial; while those same upbringing factors may force unattractive emotions to either be repressed or suppressed. This may be the reason why the biographies of many famous artists depict their lifetimes as a series of taboo-crossings – for like many rock-n-roll icons – not every lover is left alive. Felt-intuitions penetrate deeper, are both singular and personal. Art as an expression-and-communication speaks to it all.

“succinctly and evocatively”

This is where craft of the artist comes in. Every artist knows that the less said the better, that craft means being succinct. This is true in acting, in writing, in music, in dance and in the visual arts. Art succeeds when it extracts the refined essence of an intuition or an experience so effectively that it can evoke something similar in the viewer. This allows the perceiver/receiver to experience a reconstruction within the sphere of their own feeling-world – entirely without the use of concepts. Strong emotions in the perceiver may then be elicited: surprised by joy; disturbed by fear. A discovery. A release.

“a sense-based unity”

Past definitions for art may have relied on the word “form” to describe the resulting piece. But that word is inaccurate because though that piece may very well exist as a form, as a thing, as an object, what makes it art is the fact that, it is a vibrant unity created from disparate elements: thoughts, words, feelings, sensations, movements, notes, lines or splashes of paint. These sense-based communications allow the perceiver/receiver to recreate a similar unity within themselves. (again, an example of non-duality) And aesthetic pleasure resides entirely in this: the subtle recreation of an intuition or an experience so deeply felt and communicated that we too resonate with it – entirely without the use of language-based concepts. And in addition, our lived-experience becomes enhanced by this resonance.

Prachtig! (that’s great!)

Abstraction or realism: a false dichotomy?

August 31, 2020

I think any artist functioning in the twentieth/twenty-first century has had to (at least self-reflexively) address the apparent dichotomies of approach between abstraction and/or realism. Are they really as separated as they might at first appear? Personally, I don’t think so. If anything, it’s more a question of scale. Let me explain.

About forty five years ago, during my art school days, while viewing a Rembrandt self portrait in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, I had a sudden flash of insight. I realised that if you took a square inch (or two) of that painting and expanded it exponentially you might end up with a piece of modern art. Place it on the wall and voila! Just like that. But that wouldn’t work for just any painter. It would only work for someone who was a master of their craft; someone whose play of light and shadow did not ignore visual interest or luminosity in any part of the surface’s value range; someone whose sense of colour and texture appealed to the senses in a magical way; someone who left enough hints on the painting’s surface such that you, through your act of perceiving, could be left guessing, sure of your own experience, less sure of its (conceptual) meaning.

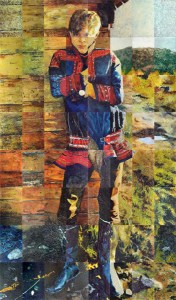

I took that insight and dove directly into learning about the materials artists have traditionally used to create paintings. I figured then, as I do now, “it ain’t what you paint but the way how you paint it”. Thus, rather than create a number of paintings based on one particular (simple) image but interpreted in different ways (like Josef Alber’ Homage to the Square, Warhol’s soup cans, or Jasper Johns’ American flags), I took one strong central image, cut it into identical parts and rendered each one separately. Each part was intended to function independently as a painting in its own right yet also to contribute to the unity of the whole. That, at least, was the theory, which worked out relatively well at the time (see linked image to the left). Yet of course becoming a master of one’s materials is not an overnight process, it’s much less dependent on a flash of insight than it is upon years of experimentation, dedication, hard work and synchronistic luck (you can’t discount that!). Ultimately that means you guide the materials (and the happy accidents). You do not control them and likewise they do not control you. For in whatever creative process any artist may be involved in, there’s always a symbiosis between the impulse and the materials; there is selection based on discrimination.

Fast forward forty five years and I can now say that I have learned a few things about what makes a painting, any painting, a good painting. One, it’s not about the subject matter in an absolute sense, it never is and never has been, that’s secondary. That’s not to say that the subject matter may inspire the artist. It can and it does, but that doesn’t make it art. What makes it art is the ability of the artist to communicate his or her feeling-experience to you the perceiver in such a way so that you feel it too. Note, the emphasis on two words, “communication” and “feeling”. Which brings us to the second point about what art actually is. I would now say that art, any art (including a good painting) is a felt-intuition succinctly and evocatively expressed/communicated as a sense-based unity. Full stop. Concepts may follow but are entirely secondary. In that sense then, realism and/or abstraction as modes of expression present a false dichotomy.

One possible reason that such a definition has been lacking is that Western philosophy has been slow to recognise that there is a universal dimension to the feeling-intelligence present within all sentient beings. That the subject-based dimension of consciousness can indeed present an aspect of universality, however veiled it may be. It reveals itself daily within the human being as the feeling aspect of consciousness. So, stay tuned for Aesthetics Part I: Gevoelsmatig-Bewustzijn.