Aboriginal Culture

June 23, 2023

Cave painting of a dancing, ritualistic figure from Jar Island – at least 30,000 years old, if not more.

After our return from Australia and before I get on with the normal activities of our life here in Europe, I feel the need to put down some thoughts and feelings about the Aboriginal people and art that I encountered there. First, the word “aboriginal” is a Latin term, roughly translating to “from the beginning”, which was categorically applied by Australia’s white settlers in the early 19th century to distinguish between themselves and the dark-skinned natives they encountered there. But just to clarify, when the settlers arrived, there were already approximately five hundred different tribes scattered throughout the land: they spoke different languages, had different rituals, ate different food (bush tucker) and had different migration habits, depending on the climate. However, as an umbrella term, it stuck. It’s usage immediately reinforced larger cultural and racial divisions which hardened over time.

Cave painting from Jar Island – at least 30,000 years old, if not more.

The dark-skinned indigenous tribes wished to continue with their hunter-gatherer way of life, sustained by the stories which had been communicated orally (mostly in secret initiatory rites) and maintained (so they claim) in an unbroken line for tens of thousands of years. In fact, the current date collaborated to by scientific archeology places the presence of hunter-gatherers at specific locations within Australia from 50,000 to 60,000 thousand years. On encountering these “dreamtime” myths and stories, primarily through the art that continues to surface, I experienced the sense of a living connection to “Country”, the term they use to describe their sense of a land animated by Spirit-Gods, immanent within the animals, birds, plants, trees, insects, rocks, water and wind. It’s an animistic group-identity connecting these people to each other and to the land through customs prescribed by the Law (the moral precepts) given to them by the first Spirit-Gods.

In contrast, the white-skinned settlers, mostly farmers and miners, were interested in the open land of the New World. They were part of the European colonial expansion already sweeping the globe. In this case, in Australia and especially in the 19th century, Britain laid claim to a land they conceived of as being empty (terra nullius). They brought with them their culture – and more effectively, their civilization. As in other areas of the New World, an orally transmitted culture of hunter-gatherers was no match to the technologies of civilization: guns, money, law, agriculture, houses, roads, and a unified and unifying language cemented by Gutenberg’s books. It was an inevitable and unstoppable wave which ultimately resulted in an indigenous culture becoming extracted from the sustaining conditions of its generation and relocated to settlements on the edges of the white fellas’ world.

Racial differences, of course, were easy markers, signposts of the deeper cultural contrasts within. In some places assimilation proceeded gently with the help of missionaries introducing the natives to their (Christian) God, agricultural methods and language (English). In other places, for a continent peopled at least in part by Victorian society’s rejects (the penal colony prisoners), the transition was much harsher. Also, and at the same time, mere physical contact with the white man meant an introduction to his diseases (things like polio, diabetes and alcoholism just to name a few). It was catastrophic to the isolated and genetically unprepared immune systems of these tribes. Thus, over approximately two hundred plus years, the attrition brought on by war, disease and displacement caused profound challenges to the identity of these people. Within the settlements, there was not only a decimated population, there was also a listlessness and general lack of purpose which at times threatened to wipe these people off the planet. The story could have stopped there but it didn’t. There’s always a swing of the pendulum.

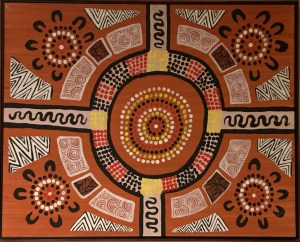

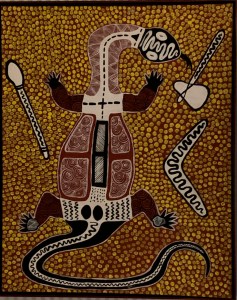

Aboriginal art from our hotel room in Broome.

Over the centuries, as cultural assimilation (slowly) proceeded and an aversion to (overt) racism grew, the more difficult challenge of overcoming cultural chauvinism loomed (and still does, though to a much lesser degree). The later half of the twentieth century had seen a general increase in public interest for the situation of the indigenous Australians, while for the latter, through the more general acquisition of the English language as well as becoming educated in Australian law, came the opportunity to challenge it. At root is/was the issue of ownership: political ownership and/or cultural ownership, where they meet and where they do not. In Australia, as culture and politics slowly change, two events of the last fifty years stand out.

Aboriginal art from our hotel room in Broome.

The first change was cultural. Sometime in the 1970’s, when an art teacher (Geoffrey Bardon) in an indigenous settlement north and west of Alice Springs (Papunya) noticed his young students drawing patterns in the sand, he encouraged them to paint and draw these forms and shapes – which they did. Before that they had been copying the images of cowboys and Indians from TV and films. Soon the elders, who had been watching from the sidelines, began requesting paint and canvases for themselves, too. “Aboriginal art”, as a movement, had been born. That’s a simplistic explanation – and from an external perspective – but perhaps for an indigenous human being steeped in Dreamtime stories (invoking a reality perceived as concurrent to the conditions of life within the shacks of a settlement) turning to these stories was like turning on the spigot to a source of fresh water: easy, natural, and virtually effortless. For myself, as both philosopher and artist, I tend to think that if it had not been for Picasso, Freud and/or Jung impacting the world of western culture in the early part of the twentieth century as they did, what was and is being communicated from the sidelined Aboriginal cultural world would not have received the appreciation that it has. For example, besides exhibitions in major galleries and art centers around the world, currently there is a wing dedicated to Aboriginal art in the National Museum in Canberra.

The second event, just as transformative, was political. In 1992, in the Mabo vs Queensland decision, the Supreme Court of Australia overturned the terra nullius precedent which had been used by England to justify its seizure of land during the continent’s colonial era. Challenging this precedent had put the Indigenous People in the strange position of needing to prove something legally that – but for vested interests – was generally acknowledged as common-sense. In 1993, this decision was quickly followed by the Australian Parliament’s passing of the Native Title Act. The NTA sought “to provide a national system for the recognition and protection of native title and for its co-existence with the national land management system”. Of course, the devil was in the details. As a Belgian lawyer once quipped to me: “Possession is nine tenths of the law”. So, the NTA opened the door but did not grant entry. Legal challenges continue to be an ongoing process within the states and territories: claims are mounted for landmarks deemed especially valuable to the local tribes; citizens, mining companies and pastoral concerns fight back. Thus you have, in modern day Australia, an on-going political/legal situation. Who owns what? And who has the right to decide it?

During our visit in May 2023, before a classical music concert in Sydney, we were surprised to hear an acknowledgement of tribute to the local tribe as traditional owners of the land on which Sydney’s Opera House stood. Later, the same occurred in Perth. On the entry walls in the Art Museums of both Sydney and Perth, we read the same – in so many words. During our stay in Perth, we noticed banners proclaiming 2023 as the “Year of Reconciliation”. While on a Friday, as we traveled by bus to King’s Park we encountered a number of young friendly Aboriginal kids excitedly journeying to the “Walk of Reconciliation”, a festival taking place there that day. As we wandered through the park’s natural beauty, we noticed stations set up for demonstrations of indigenous music, dance, painting, pottery, weaving and bush tucker. Cool.

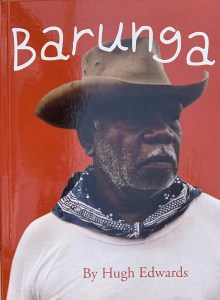

Albert Barunga by Hugh Edwards.

Later, in our hotel, I finished reading the biography of a native man named Albert Barunga. I had picked it up after conversing with his grandson, Warren Barunga, in a shack off Freshwater Cove in the Kimberley. There, Warren was selling a few books, his art-work and that of some other clan members. His grandfather, Albert Barunga had been an Aboriginal man raised in the bush sometime during the 1920’s. Later he was educated by missionaries. During his lifetime he had achieved success through his ability to function well in both worlds. He helped to translate parts of the New Testament into his native Worora tribal language. He was skilled in managing horses, boats and people and worked as a scout for the Australian navy in WWII. Later he functioned as an advocate for his tribe. In 1977, he and his wife were invited to meet the Queen of England when her yacht was moored off the coast. Though the book was an interesting biography, documenting the particulars of a transition from a hunter-gatherer way of life to a (western) civilized one, one passage in particular stood out to me. It highlights a difference in the method-of-knowing emphasized by these contrasting cultural environments.

He described an experience which occurred during the Second World War. He was about to board a Catlina flying-boat airplane heading out on patrol. He had never flown before and so was excited about the opportunity, however as he approached the plane, a cold feeling came over him. His aversion was noticed by the Captain who simply suggested “Perhaps another time, Albert”. So, he remained behind, despondent at his “failure”, only to hear hours later that the plane had been shot down by the Japanese, losing all fifteen crew members. He remembered then the cold feeling and concluded: “something told me it was a death ship. I can’t explain what it was. […] This kind of feeling is not uncommon with Aboriginals. A sixth sense, the white men call it. When I was younger and closer to the bush I had it much more strongly. [..] But the white man has rubbed across my brain and these sensitive things have gone. Now we are away from our own country, the spirit-feelings don’t come back.”

Douwe Tiemersma

Douwe Tiemersma, our Dutch-language-based teacher of non-duality, earned an interdisciplinary PhD in the fields of biology and philosophy. So of course he was an accomplished scholar within reason-based methods-of-knowing. But as a teacher of non-duality and a lifelong practitioner of yoga and meditation, he was particularly keen to emphasize the importance of a gevoelsmatig kind-of-knowing. Gevoelsmatig then refers to a sensitive, intuitive, instinct-type of feeling-knowing that is not only fundamental to all forms of art but to existence itself. For my husband and I, as his English language translators, we often found it difficult to translate the word “gevoelsmatig” into English – using just one word. It refers then to an inception, a feeling-knowing which may be based on sensations, emotions, or impressions not entirely understood and so (at least to the subject, but also to others) may appear irrational. In Dutch, “gevoelens” are feelings, “gevoelig” refers to being sensitive, so these channels of communication play a nuanced role in the word “gevoelsmatig”, however in English, if you use “instinct” or “intuition”, the main etymological clue is the prefix “in”, which points internally without much of a clue about which channel of communication may be involved. Additionally, if you use “feeling” or “emotion”, the sense that it is a subtle mode of intelligent communication may be less apparent.

Also, as Albert Barunga noticed about his intuition, it’s something that an individual (and his or her living conditions) can either encourage or discourage – but never entirely eradicate. It creeps up on us in our dreams, the shadowed world of our daytime neglect. The non-dual perspective suggests it’s intrinsic to human nature and complimentary to reason. On the cultural level then this tends to surface as our collective and recurring myths. Thus, within western culture, particularly in the twentieth and twenty-first century, as science and philosophy have proceeded to demythologize religion, Picasso, Freud, Jung and now Aboriginal art, through psychology and art, have given myth a heightened value. To a mind focused exclusively on reason as a method-of-knowing, subtly felt intuitions may appear as magical thinking, yet to a mind open to alternatives, a good intuition may indeed tell reason where to dig. To my mind it’s a question of balance, personally and culturally.

February 16, 2024 at 10:33 am

It’s an informative article. Like it:)))